“If we were eating what the government actually funded in agricultural supports, we’d be having a giant corn fritter, deep fried in soybean oil. And it’s like, that’s not exactly what we should be eating.”

~ Mark Hyman

A couple years back (2018), researchers did an analysis of long-term data on intake of carbohydrates, plant foods, and animal foods: Sara B Seidelmann, et al, Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis). The data, however, turns out to be more complicated than how it was reported in the mainstream news and in other ways over-simplified.

This was an epidemiological study of 15,000 people done with notoriously unreliable self-reports called Food Frequency Questionnaires based on the subjects’ memory of years of eating habits. The basic conclusion was that a diet moderate in carbs is the healthiest. That reminds me of the “controlled carbs” that used to be advocated to ‘manage’ diabetes that, in fact, worsened diabetes over time (American Diabetes Association Changes Its TuneAmerican Diabetes Association Changes Its Tune) — what was being managed was slow decline leading to early death. Why is it the ruling elite and its defenders, whether talking about diet or politics, always trying to portray extreme positions as ‘moderate’?

Let’s dig into the study. Although the subjects were seen six times over a 25 year period, the questionnaire was given only twice with the first visit in the late 1980s and with the third visit in the mid 1990s — two brief and inaccurate snapshots with the apparent assumption that dietary habits didn’t change from the mid 1990s to 2017. As was asked of the subjects, do you recall your exact dietary breakdown for the the past year? In my personal observations, many people can’t recall what they ate last week or sometimes even what they had the day before — the human memory is short and faulty (the reason nutritionists will have patients keep daily food diaries).

There was definitely something off about the data. When the claimed total caloric intake is added up it would’ve meant starvation rations for many of the subjects, which is to say they were severely underestimating parts of their diet, most likely the parts of their diet that are the unhealthiest (snacks, fast food, etc). Shockingly, they didn’t even assess or rather didn’t include carbohydrate intake for all those periods for they later on extrapolated from the earlier data with no explanation for this apparent data manipulation.

To further problemitize the results, those who developed metabolic health conditions (diabetes, stroke, heart disease) in the duration, likely caused by carbohydrate consumption, were excluded from the study, as were those who died — it was expected and one might surmise it was intentionally designed to find no link between dietary carbs and health outcomes. That is to say the study was next to worthless (John Ioannidis, The Challenge of Reforming Nutritional Epidemiologic Research). Over 80% of the hypotheses of nutritional epidemiology are later proved wrong in clinical trials (S. Stanley Young & Alan Karr, Deming, data and observational studies).

Besides, the researchers defined low-carb as anything below 40% and very high-carb as anything above 70%, though the study itself was mainly looking at percentages in between these. This study wasn’t about the keto diet (5% carbs of total energy intake, typically 20-50 grams per day) or even generally low-carb diets (below 25%) and moderate-carb diets (25-33% or maybe slightly higher). Instead, the researchers compared diets that were varying degrees of high-carb (37-61%, about 144 grams and higher). It’s true that one might argue that, compared to the general population, a ‘moderate’-carb diet could be anything below the average high-carb levels of the standard American diet (50-60%), the high levels the researchers considered ‘moderate’ as in being ‘normal’. But with this logic, the higher the average carb intake goes the higher ‘moderate’ also becomes, a not very meaningful definition for health purposes.

Based on bad data and confounded factors for this high-carb population, the researchers speculated that diets below 37% carbs would show even worse health outcomes, but they didn’t actually have any data about low-carb diets. To put this in perspective, traditional hunter-gatherer diets tend to be closer to the ketogenic level of carb intake with, on average, 22% of dietary energy at the lower range and 40% at the highest extreme, and that is particularly ketogenic with a feast-and-fast pattern. Some hunter-gatherers, from Inuit to Masai, go long periods with few if any carbs, well within ketosis, and they don’t show signs of artherosclerosis, diabetes, etc. For hunter gatherers, the full breakdown includes 45-65% of energy from animal foods with 19-35% protein and 28-58% fat. So, on average, hunter-gatherers were getting more calories from fat than from carbs. Both the low end and high end of the typical range of fat intake is higher than the low end and high end of the typical range of carb intake.

The study simply looked at correlations without controlling for confounders: “The low carb group at the beginning had more smokers (33% vs 22%), more former smokers (35% vs 29%), more diabetics (415 vs 316), twice the native Americans, fewer habitual exercisers (474 vs 614) ” (Richard Morris, Facebook). And alcohol intake, one of the single most important factors for health and lifespan, was not adjusted for at all. Taken together, that is what is referred to as the unhealthy user bias, whereas the mid-range group in this study were affected by the healthy user bias. Was this a study of diet or a study of lifestyle and demographic populations?

On top of that, neither was data collected on specific eating patterns in terms of portion sizes, caloric intake, regularity of meals, and fasting. Also, the details of types of foods eaten weren’t entirely determined either, such as whole vs processed, organic vs non-organic, pasture-raised vs factory-farmed — and junk foods like pizza and energy bars weren’t included at all in the questionnaire; while whole categories of foods were conflated with meat being lumped together with cakes and baked goods, as separate from fruits and vegetables. A grass-finished steak or wild-caught salmon with greens from your garden was treated as nutritionally the same as a fast food hamburger and fries.

Some other things should be clarified. This study wasn’t original research but was data mining older data sets from the research of others. Also, keep in mind that it was published in the Lancet Public Health, not in the Lancet journal itself. The authors and funders paid $5,000 for it to be published there and it was never peer-reviewed. Another point is that the authors of the paper speak of ‘substitutions’: “…mortality increased when carbohydrates were exchanged for animal-derived fat or protein and mortality decreased when the substitutions were plant-based.” This is simply false. No subjects in this study replaced any foods for another. This an imagined scenario, a hypothesis that wasn’t tested. By the way, don’t these scientists know that carbohydrates come from plants? I thought that was basic scientific knowledge.

To posit that too few carbs is dangerous, the authors suggest that, “Long-term effects of a low carbohydrate diet with typically low plant and increased animal protein and fat consumption have been hypothesised to stimulate inflammatory pathways, biological ageing, and oxidative stress.” This is outright bizarre. We don’t need to speculate. In much research, it already has been shown that sugar, a carbohydrate, is inflammatory. What happens when sugar and other carbs are reduced far enough? The result is ketosis. And what is the affect of ketosis? It is an anti-inflammatory state, not to mention promoting healing through increased autophagy. How do these scientists not know basic science in the field they are supposedly experts in? Or were they purposefully cherrypicking what fit their preconceived conclusion?

Here is the funny part. Robb Wolf points out (see video below) that in the same issue of the same journal on the same publishing date, there was a second article that gives a very different perspective (Andrew Mente & Salim Yusuf, Evolving evidence about diet and health). The other study concluded a low-carb diet based on meat and animal fats particularly lowered lifespan which probably simply demonstrated the unhealthy user effect (these people were heavier, smoked more, etc), but this other article looked at other data and came to very different conclusions,

“More recently, studies using standardised questionnaires, careful documentation of outcomes with common definitions, and contemporary statistical approaches to minimise confounding have generated a substantial body of evidence that challenges the conventional thinking that fats are harmful. Also, some populations (such as the US population) changed their diets from one relatively high in fats to one with increased carbohydrate intake. This change paralleled the increased incidence of obesity and diabetes. So the focus of nutrition research has recently shifted to the potential harms of carbohydrates. Indeed, higher carbohydrate intake can have more adverse effects on key atherogenic lipoproteins (eg, increase the apolipoprotein B-to-apolipoprotein A1 ratio) than can any natural fats. Additionally, in short-term trials, extreme carbohydrate restriction led to greater short-term weight loss and lower glucose concentrations compared with diets with higher amounts of carbohydrate. Robust data from observational studies support a harmful effect of refined, high glycaemic load carbohydrates on mortality.”

Then, in direct response to the other study, the authors warned that, “The Findings of the meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution, given that so-called group thinking can lead to biases in what is published from observational studies, and the use of analytical approaches to produce findings that fit in with current thinking.” So which Lancet article should we believe? Why did the media obsess over the one while ignoring the other?

And what about the peer-reviewed PURE study that was published the previous year (2018) in the Lancet journal itself? The PURE study was much larger and better designed. Although also observational and correlative, it was the best study of its kind ever done. The researchers found that carbohydrates were linked to a shorter lifespan and saturated fat to a longer lifespan, and yet it didn’t the same kind of mainstream media attention. I wonder why.

The study can tell us nothing about low-carb diets, even if low-carb diets had been included in the study. Yet the mainstream media and health experts heralded it as proof that a low-carb diet was dangerous and a moderate-carb diet was the best. Is this willful ignorance or intentional deception? The flaws in the study were so obvious, but it confirmed the biases of conventional dietary dogma and so was promoted without question.

On the positive side, the more often this kind of bullshit gets put before the public and torn apart as deceptive rhetoric the more aware the public becomes about what is actually being debated. But sadly, this will give nutrition studies an even worse reputation than it already has. And it could discredit science in the eyes of many and could bleed over into a general mistrust of scientific experts, authority figures, and public intellectuals (e.g., helping to promote a cynical attitude of climate change denialism). This is why it’s so important that we get the science right and not use pseudo-science as an ideological platform.

* * *

Will a Low-Carb Diet Shorten Your Life?

by Chris Kresser

I hope you’ll recognize many of the shortcomings of the study, because you’ve seen them before:

- Using observational data to draw conclusions about causality

- Relying on inaccurate food frequency questionnaires (FFQs)

- Failing to adjust for confounding factors

- Focusing exclusively on diet quantity and ignoring quality

- Meta-analyzing data from multiple sources

Unfortunately, this study has already been widely misinterpreted by the mainstream media, and that will continue because:

- Most media outlets don’t have science journalists on staff anymore

- Even so-called “science journalists” today seem to lack basic scientific literacy

In light of the Aug 16th, 2018 Lancet study on carbohydrate intake and mortality, where do you see the food and diet industry heading? (Quora)

Answered by Chris Notal

A study where the conclusion was decided before the data.

They mentioned multiple problems in their analysis, but then ignored this in their introduction and conclusion.

The different cohorts: the cohort with the lowest consumption of carbs also had more smokers, more fat people, more males, they exercised less, and were more likely to be diabetic; each of these categories independently of each other more likely to result in an earlier death. Also, recognize that for the past several decades we have been told that if you want to be healthy, you eat high carb and low fat. So even if that was false, you have people with generally healthier habits period who will live longer than those who do their own thing and rebel against healthy eating knowledge of the time. For example, suppose low carb was actually found to be healthier than high carb: it wouldn’t be sufficient to offset the healthy living habits of those who had been consuming high carb.

Also, look at the age groups. The starting ages were 46–64. And it covered the next 30 years. Which meant they were studying how many people live into their 90’s. Who’s more likely to live into their 90’s, a smoker or non-smoker? Someone who is overweight or not? Males or females? Those who exercise or those who don’t? The problem is that each variable they used in the study along with high carb, on their own supports living longer than the opposite.

Carbs, Good for You? Fat Chance!

By Nina Teicholz

A widely reported study last month purported to show that carbohydrates are essential to longevity and that low-carb diets are “linked to early death,” as a USA Today headline put it. The study, published in the Lancet Public Health journal, is the nutrition elite’s response to the challenge coming from a fast-growing body of evidence demonstrating the health benefits of low-carb eating…

The Lancet authors, in recommending a “moderate” diet of 50% to 60% carbohydrates, essentially endorse the government’s nutrition guidelines. Because this diet has been promoted by the U.S. government for nearly 40 years, it has been tested rigorously in NIH-funded clinical trials involving more than 50,000 people. The results of those trials show clearly that a diet of “moderate” carbohydrate consumption neither fights disease nor reduces mortality.

Deflating Another Dietary Dogma

By Dan Murphy

Just the linking of “carbohydrate intake” and “mortality” tells you all you need to know about the authors’ conclusions, and Teicholz pulls no punches in challenging their findings, calling them “the nutrition elite’s response to the challenge coming from a fast-growing body of evidence demonstrating the health benefits of low-carb eating.”

By way of background, Teicholz noted that for decades USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans have directed people to increase their consumption of carbohydrates and avoid eating fats. “Despite following this advice for nearly four decades, Americans are sicker and fatter than ever,” she wrote. “Such a record of failure should have discredited the nutrition establishment.”

Amen, sister.

Teicholz went on to explain that even though the study’s authors relied on data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) project, which since 1987 has observed 15,000 middle-aged people in four U.S. communities, their apparently “robust dataset” is something of an illusion.

Why? Because the ARIC relied on suspect food questionnaires. Specifically, the ARIC researches used a form listing only 66 food items. That might seem like a lot, but such questionnaires typically include as many as 200 items to ensure that respondents’ recalls are accurate.

“Popular foods such as pizza and energy bars were left out [of the ARIC form],” Teicholz wrote, “with undercounting of calories the inevitable result. ARIC calculated that participants ate only 1,500 calories a day — starvation rations for most.”

Low carbs and mortality

by John Schoonbee

An article on carbohydrate intake and mortality appeared in The Lancet Public Health last week. It is titled “Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis”. In the summary of the article, the word “association” occurs 6 times. The words “cause”, “causes” or “causal” are not used at all (except as part of “all-cause mortality”).

Yet the headlines in various news outlets are as follows:

BBC : “Low-carb diets could shorten life, study suggests”

The Guardian : “Both low- and high-carb diets can raise risk of early death, study finds”

New Scientist : “Eating a low-carb diet may shorten your life – unless you go vegan too”

All 3 imply active causality. Time Magazine is more circumspect and perhaps implies more of the association noted in the article : “Eating This Many Carbs Is Linked to a Longer Life”. These headline grabbing tactics are part of what makes nutritional science so frustratingly hard. A headline could perhaps have read : “An association with mortality has been found with extreme intakes of carbohydrates but no causality has been shown”

To better understand what an association in this context means, it is perhaps good to use 2 examples. One a bit silly, but proves the point, the other more nuanced, and in fact a very good illustration of the difference between causality and association.

Hospitals cause people to die. Imagine someone saying being in hospital shortens your life span, or increases your mortality. Imagine telling a child going for a tonsillectomy this! Of course people who are admitted to hospital have a higher mortality risk than those (well people) not admitted because they are generally sicker. This is an association, but it’s not causal. Being in a hospital does not cause death, but is associated with increased death (of course doctor-caused iatrogenic deaths and multidrug resistant hospital bugs alters this conversation).

A closer example which more parallels the the Lancet Public Health article, is when considering mortality among young smokers, men particularly. Young men who smoke have a higher mortality risk, mostly related to accidental death. Does this mean smoking causes increased deaths in young men? Clearly the answer is NO. But smoking is certainly associated with an increased death rate in young men. Why? Because these young men who smoke have far higher risk taking profiles and personalities, leading to more risk taking behavior including higher risk driving styles. Using a product that has severe health warnings and awful pictures, with impunity, clearly indicates a certain attitude towards risk. They are dying more because of their risk taking behavior which is associated with a likelihood of smoking. But it’s not the smoking of cigarettes that is killing them when they are young. (When they are older, the cancer and heart disease is of course caused by the cigarette smoking, but at an earlier age, that is not the case.)

The guidelines for “healthy” eating since the late 1970’s (which were not evidence based) have stipulated a certain proportion carbohydrate intake. Guidelines have typically also biased plants as being healthier than animal sources of protein and fat. In this context then, “healthy eating” is understood to be consuming 50-55% of carbohydrates, and having less animal products, and more plants, as general rules. It means those who then choose to ignore these guidelines – hence eat far higher amounts of animal fat and protein – would conceivably be those that are snubbing generally accepted “good health” advice (whether evidence based or not) and who probably do not care as much about their health. Their lifestyles would not unreasonably therefore be expected to be unhealthier in general.

The Lancet Public Health article shows that in the quintile of their study participants having the least amount of carbohydrate intake, they significantly

- are more likely to be male

- smoke more

- exercise less

- have higher bmi’s and

- are more likely to be diabetic.

“Those eating the least carbohydrates smoked more, exercised less, were more overweight, and were more likely to be diabetic”

This seems to confirm an unhealthy user bias. Interestingly the authors also note that “the animal-based low carbohydrate dietary score was associated with lower average intake of both fruit and vegetables“. Ignoring conventional wisdom around the health of fruit and vegetables reaffirms the data and conclusion that the low carb intake group lack a certain healthy mindset.

Low, moderate or high carbohydrate?

by Zoe Harcombe

In 1977 the Senator McGovern committee issued some dietary goals for Americans (Ref 1). The first goal was “Increase carbohydrate consumption to account for 55 to 60 percent of the energy (caloric) intake.” This recommendation did not come from any evidence related to carbohydrate. It was the inevitable consequence of setting a dietary fat guideline of 30% with protein being fairly constant at 15%.

Call me suspicious, but when a paper published 40 years later, in August 2018, concluded that the optimal intake of carbohydrate is 50-55%, I smelled a rat. The study, published in The Lancet Public Health (Ref 2), also directly contradicted the PURE study, which was published in The Lancet, in August 2017 (Ref 3). No wonder people are confused. […]

I wondered what kind of person would be consuming a low carbohydrate diet in the late 1980s/early 1990s (when the 2 questionnaires in a 25 year study were done). The characteristics table in the paper tells us exactly what kind of person was in the lowest carbohydrate group. They were far more likely to be: male; diabetic; and current smokers; and far less likely to be in the highest exercise category. The ARIC study would adjust for these characteristics, but, as I often say, you can’t adjust for a whole type of person.

The groups have been subjectively chosen – not even the carb ranges are even. Most covered a 10% range (e.g. 40-50%), but the range chosen for the ‘optimal’ group (50-55%) was just 5% wide. This placed as many as 6,097 people in one group and as few as 315 in another.

This is the single biggest issue behind the headlines.

The subjective group divisions introduced what I call “the small comparator group issue.” This came up in the recent whole grains review (Ref 6). I’ll repeat the explanation here, and build on it, as it’s crucial to understanding this paper.

If 20 children go skiing – 2 of them with autism – and 2 children die in an avalanche – 1 with autism and 1 without – the death rate for the non-autistic children is 1 in 18 (5.5%) and the death rate for the autistic children is 1 in 2 (50%). Can you see how bad (or good?) you can make things look with a small comparator group?

From subjective grouping to life expectancy headlines

For the media headlines “Low carb diets could shorten life, study suggests” (Ref 5), the researchers applied a statistical technique (called Kaplan-Meier estimates) to the ARIC data. This is entirely a statistical exercise – we don’t know when people will die. We just know how many have died so far.

This exercise resulted in the claim “we estimated that a 50-year-old participant with intake of less than 30% of energy from carbohydrate would have a projected life expectancy of 29·1 years, compared with 33·1 years for a participant who consumed 50–55% of energy from carbohydrate… Similarly, we estimated that a 50-year-old participant with high carbohydrate intake (>65% of energy from carbohydrate) would have a projected life expectancy of 32·0 years, compared with 33·1 years for a participant who consumed 50–55% of energy from carbohydrate.”

Do you see how both of these claims have used the small comparator group extremes (<30% and >65%) to make the reference group look better?

Back to the children skiing… If we were to use the data we have so far (50% of autistic children died and 5.5% of non-autistic children died) and to extrapolate this out to predict survival, life expectancy for the autistic children would look catastrophic. This is exactly what has happened with the small groups – <30% carb and >65% carb – in this study.

The data have been manipulated.

When Bad Science Can Harm You

by Angela Stanton

“Statistical Analysis

We did a time varying sensitivity analysis: between baseline ARIC Visit 1 and Visit 3, carbohydrate intake was calculated on the basis of responses from the baseline FFQ. From Visit 3 onwards, the cumulative average of carbohydrate intake was calculated on the basis of the mean of baseline and Visit 3 FFQ responses…”

WOW, hold on now. They collected carbohydrate information from the first and third visit and then they estimated the rest based on these two visits? Do they mean by this that

- The data for years 2,4,5, and 6 didn’t match what they wanted to see?

- The data for years 2,4,5, and 6 didn’t exist?

What kind of a trick might this hide? Not the kind of statistics I would like to consider as VALID STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

“…WWhen Bad Science Can Harm You

Angela A Stanton, Ph.D. Angela A Stanton, to reduce potential confounding from changes in diet that could arise from the diagnosis of these diseases… The expected residual years of survival were estimated…”

Oh wow! So those who ate a lot of carbohydrates and developed diabetes, stroke, heart disease during the study were excluded? This does not reduce confounding changes but actually increases them. That is because the very thing they are studying is how carbohydrates influence health and longevity, that is no diabetes, no strokes, and no heart disease. By excluding those that actually ended up with them completely changes the outcome to the points the authors are trying to make rather than reflect the reality.

Also, if they presume a change in diet for these participants, why not for the rest? Do you detect any problems here? I do! […]

There are 3 types of studies on nutrition:

- Bad

- Good

- Meaningless–meaning it repeats something that was already repeated hundreds of times

This study falls into Bad and Meaningless nutrition studies. It is actually not really science–these researchers simply cracked the same database that others already have and manipulated the data to fit their hypothesis.

I have commented all through the quotes from the study of what was shocking to read and see. What is even more amazing is the last 2 sentences, a quote, in the press release by Jennifer Cockerell, Press Association Health Correspondent:

Dr Ian Johnson, emeritus fellow at the Quadram Institute Bioscience in Norwich, said: ‘The national dietary guidelines for the UK, which are based on the findings of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, recommend that carbohydrates should account for 50% of total dietary energy intake. In fact, this figure is close to the average carbohydrate consumption by the UK population observed in dietary surveys. It is gratifying to see from the new study that this level of carbohydrate intake seems to be optimal for longevity.‘”

It is not gratifying but horrible to see that the UK, one of the most diseased countries on the planet today, plagued by type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heart disease, should consider its current general carbohydrate consumption levels to be ideal and finds support in this study for what they are currently doing.

I suppose that if type 2 diabetes, obesity, and other metabolic diseases is what the country wants (and why wouldn’t it want that? Guess who profits from sick people?), then indeed, a 50% carbohydrate diet is ideal.

Latest Low-Carb Study: All Politics, No ScienceLatest Low-Carb Study: All Politics, No Science

by Georgia Ede

Where’s the Evidence?

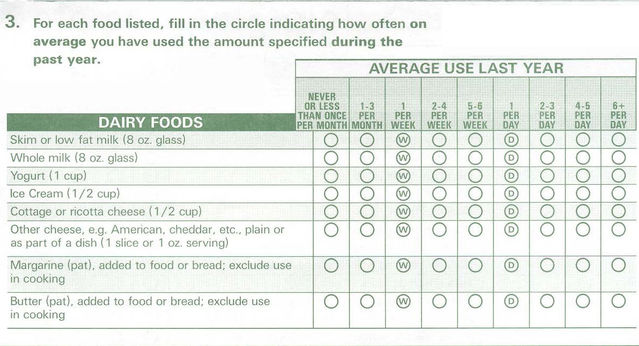

Ludicrous Methods. The most important thing to understand is that this study was an “epidemiological” study, which should not be confused with a scientific experiment. This type of study does not test diets on people; instead, it generates guesses (hypotheses) about nutrition based on surveys called Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQs). Below is an excerpt from the FFQ that was modified for use in this study. How well do you think you could answer questions like these?

How is anyone supposed to recall what was eaten as many as 12 months prior? Most people can’t remember what they ate three days ago. Note that “I don’t know” or “I can’t remember” or “I gave up dairy in August” are not options; you are forced to enter a specific value. Some questions even require that you do math to convert the number of servings of fruit you consumed seasonally into an annual average—absurd. These inaccurate guesses become the “data” that form the foundation of the entire study. Foods are not weighed, measured, or recorded in any way.

The entire FFQ used contained only 66 questions, yet the typical modern diet contains thousands of individual ingredients. It would be nearly impossible to design a questionnaire capable of capturing that kind of complexity, and even more difficult to mathematically analyze the risks and benefits of each ingredient in any meaningful way. This methodology has been deemed fatally flawed by a number of respected scientists, including Stanford Professor John Ioannidis in this 2018 critique published by JAMA.

Missing Data. Between 1987 and 2017, researchers met with subjects enrolled in the study a total of six times, yet the FFQ was administered only twice: at the first visit in the late 1980s and at the third visit in the mid-1990s. Yes, you read that correctly. Did the researchers assume that everyone in the study continued eating exactly the same way from the mid-1990s to 2017? Popular new products and trends surely affected how some of them ate (Splenda, kale chips, or cupcakes, anyone?) and drank (think Frappucinos, juice boxes, and smoothies). Why was no effort made to evaluate intake during the final 20-plus years of the study? Even if the FFQ method were a reliable means of gathering data, the suggestion that what individuals reported eating in the mid-1990s would be directly responsible for their deaths more than two decades later is hard to swallow.

There are other serious flaws to cover below, but the two already listed above are reasons enough to discredit this study. People can debate how to interpret the data until the low-carb cows come home, but I would argue that there is no real data in this study to begin with. The two sets of “data” are literally guesses about certain aspects of people’s diets gathered on only two occasions. Do these researchers expect us to believe they accurately represent participants’ eating patterns over the course of 30 years? This is such a preposterous proposition that one could argue not only that the data are inaccurate, but that they are likely wildly so.

Learn why we think you should QUESTION the results of the recent Lancet study which suggests that a low carb diet is bad for your health.

by Tony Hampton

1) Just last year, the Lancet published a more reliable study with over 120,000 participates entitled Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. This study involved participates actually visiting a doctors office where various biomarkers were tracked. Here is the link to this study: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32252-3/abstract In this study, high carbohydrate intake was associated with higher risk of total mortality, whereas total fat and individual types of fat were related to lower total mortality. This is consistent with Dr. Hope and my recommendation to consume a lower carb high-fat diet.

2) Unlike the PURE study, the new Lancet study containing only 15,428 participates entitled Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis used food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) containing 66 questions asking participates what they ate previously. This is not as reliable as a randomized control trial where participants are divided by category into separate groups to compare interventions and are fed specific diets. Using FFQ is simply not reliable. Can you remember what you ate last week or over the last year? FFQ also are unreliable because participates tend to downplay their bad eating habits and describe what they think the researchers want to hear. FFQ are simply inherently inaccurate compared to randomized control trails and allow participates to self-declare themselves as eating low carb in this study.

3) Of the groups participating in the new Lancet study, the lower carb group’s participates were the least healthy of the study participates with higher rates of smokers (over 70% smoked or previously smoked), diabetics, overweight, and those who exercised less. This was not true of the other group’s participates.

4) The so-called low carb group at less than 40% carbs is not really a low carb diet. The participates in this group consuming 35-40% carbs are consuming nearly 200 carbs per day. Many of our patients on a low carb diet are consuming less than 50 carbs per day. So are the participates in this study really on a low carb diet? We would suggest they are not.

5) Declaration of interests: When Dr. Hope and I learned to review research studies, the first question we were taught to ask was: who funded the study. If you click on the study link above and go to the bottom of the study, you will see under the declaration of interest section that there were some personal fees from two pharmaceuticals (Novartis and Zogenix). Pharmaceuticals provide needed resources to fund much-needed research. The big message here, however, is full disclosure. Just as I discussed at the beginning of this post, Dr. Hope and I are somewhat biased towards a low carb high-fat diet. We felt you needed to be aware of this as you read this post. You also need to know who funded the Lancet study we are discussing. You decide how to use that information.

6) The Lancet study is an observational study. Observational studies only show an association, not causation. Association is weak science and should always be questioned.

7) The moderate carb diet in this study was associated with the lowest mortality. In this study, participates ate a diet with 50-55% carbs. This mirrors the current USDA diet which has been recommended over the last 40 plus years. During this timeline, Americans followed the USDA recommendations and reduced saturated fat while increasing carbs in their diets. This led to the onset of the obesity epidemic. Let us not go back to recommendations which have not worked.

8) Media sensationalism and bias. I know it’s frustrating to keep hearing mixed messages and dramatic headlines but this is how the media gets your attention, so don’t be convinced by headlines. If you are still reading at this point in the post, you won’t be sidetracked by dramatic press releases.

STUDY: Do Low Carb Diets Increase Mortality?

by Siim Land

Here’s my debunking:

- The “low carb group” wasn’t actually low carb and had a carb intake of 37% of total calories…It’s much rather moderate carb

- “Low carb participants” were more sedentary, current smokers, diabetics, and didn’t exercise

- The study was conducted over the course of 25 years with follow-ups every few years

- No real indication of what the people actually ate in what amounts and at what macronutrient ratios

- The same applies to the increased mortality rates in high carb intake – no indication of food quality of carb content

- Correlation does not equal causation

- Animal proteins and fats contributed more to mortality than plant-based foods, which again doesn’t take into account food quality and quantities

- It’s true that too much of anything is bad and you don’t want to eat too many carbs, too much fat, too much meat, or too much protein…

Is Keto Bad For You? Addressing Keto ClickBait

by Chelsea Malone

Where Did the Study Go Wrong?

- This was not a controlled study. Other factors that influence lifespan like physical activity, stress levels, and smoking habits were recorded, but not adjusted for. The “low-carb” group also consisted of the highest amount of smokers and the lowest amount of total physical activity conducted.

- The data collection process left plenty of room for errors. In order to collect the data on total carbohydrate consumption, participants were given a questionnaire (FFQ) where they indicated how often they ate specific foods on a list over the past several years. Most individuals would not be able to accurately recall total food consumption over such a long period of time and were likely filled with errors.

- Consuming under 44% of total daily calories from carbohydrates was considered low carb. To put this into perspective, if the average person consumes 2,000 calories a day, that is 220 grams of carbohydrates. This is nowhere near low-carb or keto territory.

- This study is purely correlational, and correlation does not equal causation. Think of it like this: If a new study was published showing individuals who wear purple socks were more likely to get into a car crash than individuals wearing red socks, would you assume that purple socks cause car accidents? You probably wouldn’t and the same principle applies to this study.

#Fakenews Headlines – Low Carb Diets aren’t Dangerous!

by Belinda Fettke

Not only was the data cherry-picked from a Food Frequency Questionnaire that lumped ‘meat in with the cakes and baked goods’ category while dairy, fruit, and vegetables were all kept as separate entities (implying that meat is a discretionary and unhealthy food??), they also excluded anyone who became metabolically unwell over the 25 year period since the study began (but not from baseline). […]

Dr Aseem Malhotra took it to another level in his interview on BBC World News.

Here are a couple of Key Points he outlined on Facebook:

1. Reviewing ALL the up to date evidence the suggestion that low carb diets shorten lifespan from this fatally flawed association study is COMPLETELY AND TOTALLY FALSE. To say that they do is a MISCARRIAGE OF SCIENCE!

2. The most effective approach for managing type 2 diabetes is cutting sugar and starch. A systematic review of randomised trials … reveals its best for blood glucose and cardiovascular risk factors in short AND long term. […]

The take-away message is please don’t believe everything that is written about the latest study to come out of Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health. The authors/funders of this paper; Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis paid $5,000 to be published in the Lancet Public Health (not to be confused with the official parent publication – The Lancet). While it went past an editorial committee it has not yet been peer reviewed.

Low-carb or high carb diet: What I want you to know about the ‘healthiest diet’, as an NHS Doctor

by Dr Aseem Malhotra

1418: Jimmy Moore Rant On Anti-Keto Lancet Study

from The Livin’ La Vida Low-Carb Show