Let me make an argument about (hyper-)individualism, rigid egoic boundaries, and hence Jaynesian consciousness (about Julian Jaynes, see other posts). But I’ll come at it from a less typical angle. I’ve been reading much about diet, nutrition, and health. With agriculture, the entire environment in which humans lived was fundamentally transformed, such as the rise of inequality and hierarchy, concentrated wealth and centralized power; not to mention the increase of parasites and diseases from urbanization and close cohabitation with farm animals (The World Around Us). We might be able to thank early agricultural societies, as an example, for introducing malaria to the world.

Maybe more importantly, there are significant links between what we eat and so much else: gut health, hormonal regulation, immune system, and neurocognitive functioning. There are multiple pathways, one of which is direct, connecting the gut and the brain: nervous system, immune system, hormonal system, etc — with the affect of diet and nutrition on immune response, including leaky gut, consider the lymphatic-brain link (Neuroscience News, Researchers Find Missing Link Between the Brain and Immune System) with the immune system as what some refer to as the “mobile mind” (Susan L. Prescott & Alan C. Logan, The Secret Life of Your Microbiome, pp. 64-7, pp. 249-50). As for a direct and near instantaneous gut-brain link, there was a recent discovery of the involvement of the vagus nerve, a possible explanation for the ‘gut sense’, with the key neurotransmitter glutamate modulating the rate of transmission in synaptic communication between enteroendocrine cells and vagal nerve neurons (Rich Haridy, Fast and hardwired: Gut-brain connection could lead to a “new sense”), and this is implicated in “episodic and spatial working memory” that might assist in the relocation of food sources (Rich Haridy, Researchers reveal how disrupting gut-brain communication may affect learning and memory). The gut is sometimes called the second brain because it also has neuronal cells, but in evolutionary terms it is the first brain. To demonstrate one example of a connection, many are beginning to refer to Alzheimer’s as type 3 diabetes, and dietary interventions have reversed symptoms in clinical studies. Also, gut microbes and parasites have been shown to influence our neurocognition and psychology, even altering personality traits and behavior such as with toxoplasma gondii. [For more discussion, see Fasting, Calorie Restriction, and Ketosis.]

The gut-brain link explains why glutamate as a food additive might be so problematic for so many people. Much of the research has looked at other health areas, such as metabolism or liver functioning. It would make more sense to look at its effect on neurocognition, but as with many other particles many scientists have dismissed the possibility of glutamate passing the blood-brain barrier. Yet we now know many things that were thought to be kept out of the brain do, under some conditions, get into the brain. After all, the same mechanisms that cause leaky gut (e.g., inflammation) can also cause permeability in the brain. So, we know the mechanism about how this could happen. Evidence is pointing in this direction: “MSG acts on the glutamate receptors and releases neurotransmitters which play a vital role in normal physiological as well as pathological processes (Abdallah et al., 2014[1]). Glutamate receptors have three groups of metabotropic receptors (mGluR) and four classes of ionotropic receptors (NMDA, AMPA, delta and kainite receptors). All of these receptor types are present across the central nervous system. They are especially numerous in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala, where they control autonomic and metabolic activities (Zhu and Gouaux, 2017[22]). Results from both animal and human studies have demonstrated that administration of even the lowest dose of MSG has toxic effects. The average intake of MSG per day is estimated to be 0.3-1.0 g (Solomon et al., 2015[18]). These doses potentially disrupt neurons and might have adverse effects on behaviour” (Kamal Niaz, Extensive use of monosodium glutamate: A threat to public health?).

One possibility to consider is the role of exorphins that are addictive and can be blocked in the same way as opioids. Exorphin, in fact, means external morphine-like substance, in the way that endorphin means indwelling morphine-like substance. Exorphins are found in milk and wheat. Milk, in particular, stands out. Even though exorphins are found in other foods, it’s been argued that they are insignificant because they theoretically can’t pass through the gut barrier, much less the blood-brain barrier. Yet exorphins have been measured elsewhere in the human body. One explanation is gut permeability (related to permeability throughout the body) that can be caused by many factors such as stress but also by milk. The purpose of milk is to get nutrients into the calf and this is done by widening the space in gut surface to allow more nutrients through the protective barrier. Exorphins get in as well and create a pleasurable experience to motivate the calf to drink more. Along with exorphins, grains and dairy also contain dopaminergic peptides, and dopamine is the other major addictive substance. It feels good to consume dairy as with wheat, whether you’re a calf or a human, and so one wants more. Think about that the next time you pour milk over cereal.

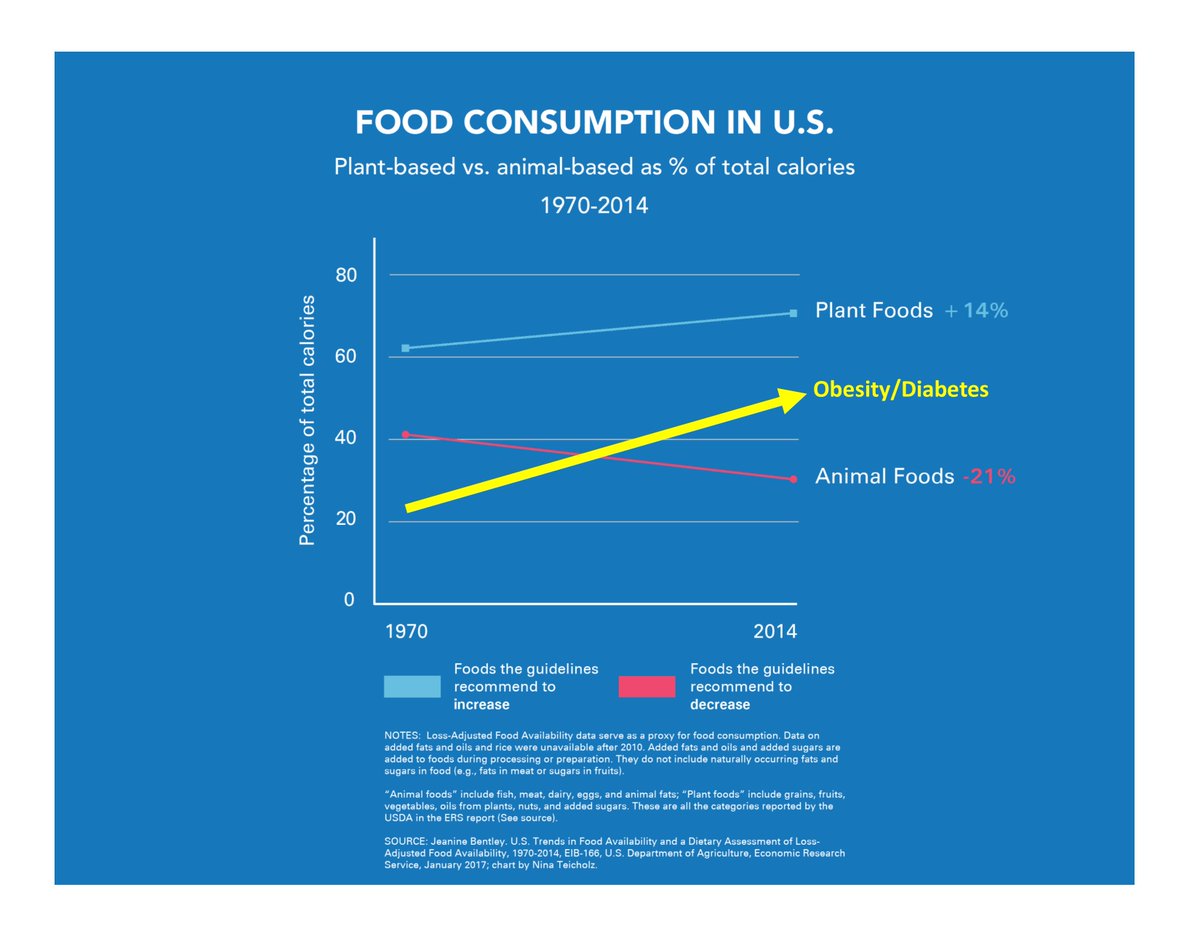

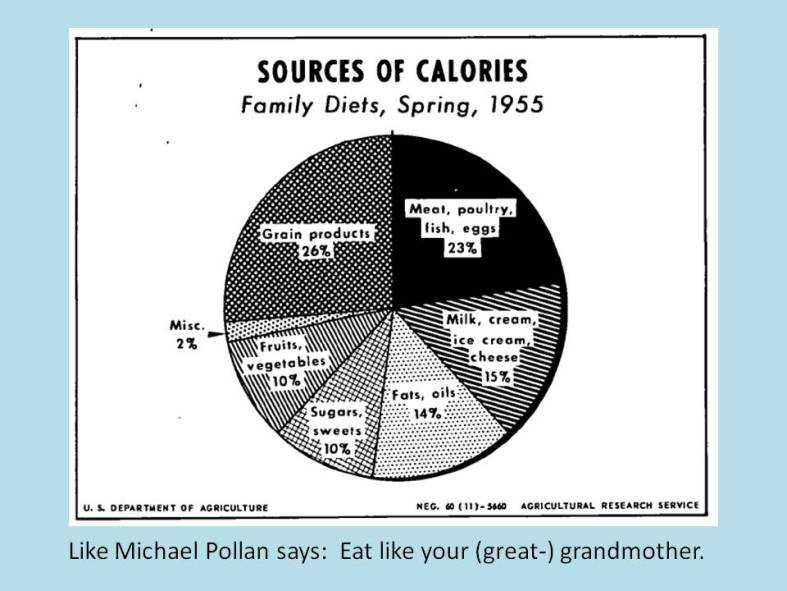

Addiction, of food or drugs or anything else, is a powerful force. And it is complex in what it affects, not only physiologically and psychologically but also on a social level. Johann Hari offers a great analysis in Chasing the Scream. He makes the case that addiction is largely about isolation and that the addict is the ultimate individual (see To Put the Rat Back in the Rat Park, Rationalizing the Rat Race, Imagining the Rat Park, & Individualism and Isolation), and by the way this connects to Jaynesian consciousness with its rigid egoic boundaries as opposed to the bundled and porous mind, the extended and enmeshed self of bicameralism and animism. It stands out to me that addiction and addictive substances have increased over civilization, and I’ve argued that this is about a totalizing cultural system and a fully encompassing ideological worldview, what some call a reality tunnel (see discussion of addiction and social control in Diets and Systems & Western Individuality Before the Enlightenment Age). Growing of poppies, sugar cane, etc came later on in civilization, as did the production of beer and wine — by the way, alcohol releases endorphins, sugar causes a serotonin high, and both activate the hedonic pathway. Also, grain and dairy were slow to catch on, as a large part of the diet. Until recent centuries, most populations remained dependent on animal foods, including wild game (I discuss this era of dietary transition and societal transformation in numerous posts with industrialization and technology pushing the already stressed agricultural mind to an extreme: Ancient Atherosclerosis?, To Be Fat And Have Bread, Autism and the Upper Crust, “Yes, tea banished the fairies.”, Voice and Perspective, Hubris of Nutritionism, Health From Generation To Generation, Dietary Health Across Generations, Moral Panic and Physical Degeneration, The Crisis of Identity, The Disease of Nostalgia, & Technological Fears and Media Panics). Americans, for example, ate large amounts of meat, butter, and lard from the colonial era through the 19th century (see Nina Teicholz, The Big Fat Surprise; passage quoted in full at Malnourished Americans). In 1900, Americans on average were only getting 10% of their calorie intake from carbohydrates and sugar was minimal, a potentially ketogenic diet considering how much lower calorie the average diet was back then.

Something else to consider is that low-carb diets can alter how the body and brain functions (the word ‘alter’ is inaccurate, though, since in evolutionary terms ketosis would’ve been the normal state; and so rather the modern high-carb diet is altered from the biological norm). That is even more true if combined with intermittent fasting and restricted eating times that would have been more common in the past (Past Views On One Meal A Day (OMAD)). Interestingly, this only applies to adults since we know that babies remain in ketosis during breastfeeding, there is evidence that they are already in ketosis in utero, and well into the teen years humans apparently remain in ketosis: “It is fascinating to see that every single child , so far through age 16, is in ketosis even after a breakfast containing fruits and milk” (Angela A. Stanton, Children in Ketosis: The Feared Fuel). “I have yet to see a blood ketone test of a child anywhere in this age group that is not showing ketosis both before and after a meal” (Angela A. Stanton, If Ketosis Is Only a Fad, Why Are Our Kids in Ketosis?). Ketosis is not only safe but necessary for humans (“Is keto safe for kids?”). Taken together, earlier humans would have spent more time in ketosis (fat-burning mode, as opposed to glucose-burning) which dramatically affects human biology. The further one goes back in history the greater amount of time people probably spent in ketosis. One difference with ketosis is that, for many people, cravings and food addictions disappear. [For more discussion of this topic, see previous posts: Fasting, Calorie Restriction, and Ketosis, Ketogenic Diet and Neurocognitive Health, Is Ketosis Normal?, & “Is keto safe for kids?”.] Ketosis is a non-addictive or maybe even anti-addictive state of mind (FranciscoRódenas-González, et al, Effects of ketosis on cocaine-induced reinstatement in male mice), similar to how certain psychedelics can be used to break addiction — one might argue there is a historical connection over the millennia between a decrease of psychedelic use and an increase of addictive substances: sugar, caffeine, nicotine, opium, etc (Diets and Systems, “Yes, tea banished the fairies.”, & Wealth, Power, and Addiction). Many hunter-gatherer tribes can go days without eating and it doesn’t appear to bother them, such as Daniel Everett’s account of the Piraha, and that is typical of ketosis — fasting forces one into ketosis, if one isn’t already in ketosis, and so beginning a fast in ketosis makes it even easier. This was also observed of Mongol warriors who could ride and fight for days on end without tiring or needing to stop for food. What is also different about hunter-gatherers and similar traditional societies is how communal they are or were and how more expansive their identities in belonging to a group, the opposite of the addictive egoic mind of high-carb agricultural societies. Anthropological research shows how hunter-gatherers often have a sense of personal space that extends into the environment around them. What if that isn’t merely cultural but something to do with how their bodies and brains operate? Maybe diet even plays a role. Hold that thought for a moment.

Now go back to the two staples of the modern diet, grains and dairy. Besides exorphins and dopaminergic substances, they also have high levels of glutamate, as part of gluten and casein respectively. Dr. Katherine Reid is a biochemist whose daughter was diagnosed with autism and it was severe. She went into research mode and experimented with supplementation and then diet. Many things seemed to help, but the greatest result came from restriction of dietary glutamate, a difficult challenge as it is a common food additive (see her TED talk here and another talk here or, for a short and informal video, look here). This requires going on a largely whole foods diet, that is to say eliminating processed foods (also see Traditional Foods diet of Weston A. Price and Sally Fallon Morell, along with the GAPS diet of Natasha Campbell-McBride). But when dealing with a serious issue, it is worth the effort. Dr. Reid’s daughter showed immense improvement to such a degree that she was kicked out of the special needs school. After being on this diet for a while, she socialized and communicated normally like any other child, something she was previously incapable of. Keep in mind that glutamate, as mentioned above, is necessary as a foundational neurotransmitter in modulating communication between the gut and brain. But typically we only get small amounts of it, as opposed to the large doses found in the modern diet. In response to the TED Talk given by Reid, Georgia Ede commented that it’s, “Unclear if glutamate is main culprit, b/c a) little glutamate crosses blood-brain barrier; b) anything that triggers inflammation/oxidation (i.e. refined carbs) spikes brain glutamate production.” Either way, glutamate plays a powerful role in brain functioning. And no matter the exact line of causation, industrially processed foods in the modern diet would be involved. By the way, an exacerbating factor might be mercury in its relation to anxiety and adrenal fatigue, as it ramps up the fight or flight system via over-sensitizing the glutamate pathway — could this be involved in conditions like autism where emotional sensitivity is a symptom? Mercury and glutamate simultaneously increasing in the modern world demonstrates how industrialization can push the effects of the agricultural diet to ever further extremes.

Glutamate is also implicated in schizophrenia: “The most intriguing evidence came when the researchers gave germ-free mice fecal transplants from the schizophrenic patients. They found that “the mice behaved in a way that is reminiscent of the behavior of people with schizophrenia,” said Julio Licinio, who co-led the new work with Wong, his research partner and spouse. Mice given fecal transplants from healthy controls behaved normally. “The brains of the animals given microbes from patients with schizophrenia also showed changes in glutamate, a neurotransmitter that is thought to be dysregulated in schizophrenia,” he added. The discovery shows how altering the gut can influence an animals behavior” (Roni Dengler, Researchers Find Further Evidence That Schizophrenia is Connected to Our Guts; reporting on Peng Zheng et al, The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice, Science Advances journal). And glutamate is involved in other conditions as well, such as in relation to GABA: “But how do microbes in the gut affect [epileptic] seizures that occur in the brain? Researchers found that the microbe-mediated effects of the Ketogenic Diet decreased levels of enzymes required to produce the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. In turn, this increased the relative abundance of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Taken together, these results show that the microbe-mediated effects of the Ketogenic Diet have a direct effect on neural activity, further strengthening support for the emerging concept of the ‘gut-brain’ axis.” (Jason Bush, Important Ketogenic Diet Benefit is Dependent on the Gut Microbiome). Glutamate is one neurotransmitter among many that can be affected in a similar manner; e.g., serotonin is also produced in the gut.

That reminds me of propionate, a short chain fatty acid and the conjugate base of propioninic acid. It is another substance normally taken in at a low level. Certain foods, including grains and dairy, contain it. The problem is that, as a useful preservative, it has been generously added to the food supply. Research on rodents shows injecting them with propionate causes autistic-like behaviors. And other rodent studies show how this stunts learning ability and causes repetitive behavior (both related to the autistic demand for the familiar), as too much propionate entrenches mental patterns through the mechanism that gut microbes use to communicate to the brain how to return to a needed food source, similar to the related function of glutamate. A recent study shows that propionate not only alters brain functioning but brain development (L.S. Abdelli et al, Propionic Acid Induces Gliosis and Neuro-inflammation through Modulation of PTEN/AKT Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder), and this is a growing field of research (e.g., Hyosun Choi, Propionic acid induces dendritic spine loss by MAPK/ERK signaling and dysregulation of autophagic flux). As reported by Suhtling Wong-Vienneau at University of Central Florida, “when fetal-derived neural stem cells are exposed to high levels of Propionic Acid (PPA), an additive commonly found in processed foods, it decreases neuron development” (Processed Foods May Hold Key to Rise in Autism). This study “is the first to discover the molecular link between elevated levels of PPA, proliferation of glial cells, disturbed neural circuitry and autism.”

The impact is profound and permanent — Pedersen offers the details: “In the lab, the scientists discovered that exposing neural stem cells to excessive PPA damages brain cells in several ways: First, the acid disrupts the natural balance between brain cells by reducing the number of neurons and over-producing glial cells. And although glial cells help develop and protect neuron function, too many glia cells disturb connectivity between neurons. They also cause inflammation, which has been noted in the brains of autistic children. In addition, excessive amounts of the acid shorten and damage pathways that neurons use to communicate with the rest of the body. This combination of reduced neurons and damaged pathways hinder the brain’s ability to communicate, resulting in behaviors that are often found in children with autism, including repetitive behavior, mobility issues and inability to interact with others.” According to this study, “too much PPA also damaged the molecular pathways that normally enable neurons to send information to the rest of the body. The researchers suggest that such disruption in the brain’s ability to communicate may explain ASD-related characteristics such as repetitive behavior and difficulties with social interaction” (Ana Sandoiu, Could processed foods explain why autism is on the rise?).

So, the autistic brain develops according to higher levels of propionate and maybe becomes accustomed to it. A state of dysfunction becomes what feels normal. Propionate causes inflammation and, as Dr. Ede points out, “anything that triggers inflammation/oxidation (i.e. refined carbs) spikes brain glutamate production”. High levels of propionate and glutamate become part of the state of mind the autistic becomes identified with. It all links together. Autistics, along with cravings for foods containing propionate (and glutamate), tend to have larger populations of a particular gut microbe that produces propionate. In killing microbes, this might be why antibiotics can help with autism. But in the case of depression, gut issues are associated instead with the lack of certain microbes that produce butyrate, another important substance that also is found in certain foods (Mireia Valles-Colomer et al, The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression). Depending on the specific gut dysbiosis, diverse neurocognitive conditions can result. And in affecting the microbiome, changes in autism can be achieved through a ketogenic diet, temporarily reducing the microbiome (similar to an antibiotic) — this presumably takes care of the problematic microbes and readjusts the gut from dysbiosis to a healthier balance. Also, ketosis would reduce the inflammation that is associated with glutamate production.

As with propionate, exorphins injected into rats will likewise elicit autistic-like behaviors. By two different pathways, the body produces exorphins and propionate from the consumption of grains and dairy, the former from the breakdown of proteins and the latter produced by gut bacteria in the breakdown of some grains and refined carbohydrates (combined with the propionate used as a food additive; and also, at least in rodents, artificial sweeteners increase propionate levels). [For related points and further discussion, see section below about vitamin B1 (thiamine/thiamin). Also covered are other B vitamins and nutrients.] This is part of the explanation for why many autistics have responded well to ketosis from carbohydrate restriction, specifically paleo diets that eliminate both wheat and dairy, but ketones themselves play a role in using the same transporters as propionate and so block their buildup in cells and, of course, ketones offer a different energy source for cells as a replacement for glucose which alters how cells function, specifically neurocognitive functioning and its attendant psychological effects.

There are some other factors to consider as well. With agriculture came a diet high in starchy carbohydrates and sugar. This inevitably leads to increased metabolic syndrome, including diabetes. And diabetes in pregnant women is associated with autism and attention deficit disorder in children. “Maternal diabetes, if not well treated, which means hyperglycemia in utero, that increases uterine inflammation, oxidative stress and hypoxia and may alter gene expression,” explained Anny H. Xiang. “This can disrupt fetal brain development, increasing the risk for neural behavior disorders, such as autism” (Maternal HbA1c influences autism risk in offspring); by the way, other factors such as getting more seed oils and less B vitamins are also contributing factors to metabolic syndrome and altered gene expression, including being inherited epigenetically, not to mention mutagenic changes to the genes themselves (Catherine Shanahan, Deep Nutrition). The increase of diabetes, not mere increase of diagnosis, could partly explain the greater prevalence of autism over time. Grain surpluses only became available in the 1800s, around the time when refined flour and sugar began to become common. It wasn’t until the following century that carbohydrates finally overtook animal foods as the mainstay of the diet, specifically in terms of what is most regularly eaten throughout the day in both meals and snacks — a constant influx of glucose into the system.

A further contributing factor in modern agriculture is that of pesticides, also associated with autism. Consider DDE, a product of DDT, which has been banned for decades but apparently it is still lingering in the environment. “The odds of autism among children were increased, by 32 percent, in mothers whose DDE levels were high (high was, comparatively, 75th percentile or greater),” one study found (Aditi Vyas & Richa Kalra, Long lingering pesticides may increase risk for autism: Study). “Researchers also found,” the article reports, “that the odds of having children on the autism spectrum who also had an intellectual disability were increased more than two-fold when the mother’s DDE levels were high.” A different study showed a broader effect in terms of 11 pesticides still in use:

“They found a 10 percent or more increase in rates of autism spectrum disorder, or ASD, in children whose mothers lived during pregnancy within about a mile and a quarter of a highly sprayed area. The rates varied depending on the specific pesticide sprayed, and glyphosate was associated with a 16 percent increase. Rates of autism spectrum disorders combined with intellectual disability increased by even more, about 30 percent. Exposure after birth, in the first year of life, showed the most dramatic impact, with rates of ASD with intellectual disability increasing by 50 percent on average for children who lived within the mile-and-a-quarter range. Those who lived near glyphosate spraying showed the most increased risk, at 60 percent” (Nicole Ferox, It’s Personal: Pesticide Exposures Come at a Cost).

An additional component to consider are plant anti-nutrients. For example, oxalates may be involved in autism spectrum disorder (Jerzy Konstantynowicz et al, A potential pathogenic role of oxalate in autism). With the end of the Ice Age, vegetation became more common and some of the animal foods less common. That increased plant foods as part of the human diet. But even then it was limited and seasonal. The dying off of the megafauna was a greater blow, as it forced humans to both rely on less desirable lean meats from smaller prey but also more plant foods. And of course, the agricultural revolution followed shortly after that with its devastating effects. None of these changes were kind to human health and development, as the evidence shows in the human bones and mummies left behind. Yet they were minor compared to what was to come. The increase of plant foods was a slow process over millennia. All the way up to the 19th century, Americans were eating severely restricted amounts of plant foods and instead depending on fatty animal foods, from pasture-raised butter and lard to wild-caught fish and deer — the abundance of wilderness and pasturage made such foods widely available, convenient, and cheap, besides being delicious and nutritious. Grain crops and vegetable gardens were simply too hard to grow, as described by Nina Teicholz in The Big Fat Surprise (see quoted passage at Malnourished Americans).

While maintaining a garden at Walden Pond by growing beans, peas, corn, turnips and potatoes, a plant-based diet (Jennie Richards, Henry David Thoreau Advocated “Leaving Off Eating Animals”) surely contributed to Henry David Thoreau’s declining health from tuberculosis in weakening his immune system from deficiency in the fat-soluble vitamins, although his nearby mother occasionally made him a fruit pie that would’ve had nutritious lard in the crust: “lack of quality protein and excess of carbohydrate foods in Thoreau’s diet as probable causes behind his infection” (Dr. Benjamin P. Sandler, Thoreau, Pulmonary Tuberculosis and Dietary Deficiency). Likewise, Franz Kafka who became a vegetarian also died from tuberculosis (Old Debates Forgotten). Weston A. Price observed the link between deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins and high rates of tuberculosis, not that one causes the other but that nutritious diet is key to a strong immune system (Dr. Kendrick On Vaccines & Moral Panic and Physical Degeneration). Besides, eliminating fatty animal foods typically means increasing starchy and sugary plant foods, which lessens the anti-inflammatory response from ketosis and autophagy and hence the capacity for healing.

It should be re-emphasized the connection of physical health to mental health, another insight of Price. Interestingly, Kafka suffered from psychological, presumably neurocognitive, issues long before tubercular symptoms showed up and he came to see the link between them as causal, although he saw it the the other way around as psychosomatic. Even more intriguing, Kafka suggests that, as Sander L. Gilman put it, “all urban dwellers are tubercular,” as if it is a nervous condition of modern civilization akin to what used to be called neurasthenia (about Kafka’s case, see Sander L. Gilman’s Franz Kafka, the Jewish Patient). He even uses the popular economic model of energy and health: “For secretly I don’t believe this illness to be tuberculosis, at least primarily tuberculosis, but rather a sign of general bankruptcy” (for context, see The Crisis of Identity). Speaking of the eugenic, hygienic, sociological and aesthetic, Gillman further notes that, “For Kafka, that possibility is linked to the notion that illness and creativity are linked, that tuberculars are also creative geniuses,” indicating an interpretation of neurasthenia among the intellectual class, an interpretation that was more common in the United States than in Europe.

The upper classes were deemed the most civilized and so it was expected they they’d suffer the most from the diseases of civilization, and indeed the upper classes fully adopted the modern industrial diet before the rest of the population. In contrast, while staying at a sanatorium (a combination of the rest cure and the west cure), Kafka stated that, “I am firmly convinced, now that I have been living here among consumptives, that healthy people run no danger of infection. Here, however, the healthy are only the woodcutters in the forest and the girls in the kitchen (who will simply pick uneaten food from the plates of patients and eat it—patients whom I shrink from sitting opposite) but not a single person from our town circles,” from a letter to Max Brod on March 11, 1921. It should be pointed out that tuberculosis sanatoriums were typically located in rural mountain areas where local populations were known to be healthy, the kinds of communities Weston A. Price studied in the 1930s; a similar reason for why in America tuberculosis patients were sometimes sent west (the west cure) for clean air and a healthy lifestyle, probably with an accompanying change toward a rural diet, with more wild-caught animal foods higher in omega-3s and lower in omega-6s, not to mention higher in fat-soluble vitamins.

The historical context of public health overlapped with racial hygiene, and indeed some of Kafka’s family members and lovers would later die at the hands of Nazis. Eugenicists were obsessed with body types in relation to supposed racial features, but non-eugenicists also accepted that physical structure was useful information to be considered; and this insight is supported, if not the eugenicist ideology, by the more recent scientific measurements of stunted bone development in the early agricultural societies. Hermann Brehmer, a founder of the sanitorium movement, asserted that a particular body type (habitus phthisicus, equivalent to habitus asthenicus) was associated with tuberculosis, the kind of thinking that Weston A. Price would pick up in his observations in physical development, although Price saw the explanation as dietary and not racial. The other difference is that Price saw “body type” not as a cause but as a symptom of ill health, and so the focus on re-forming the body (through lung exercises, orthopedic corsets, etc) to improve health was not the most helpful advice. On the other hand, if re-forming the body involved something like the west cure in changing the entire lifestyle and environmental conditions, it might work by way of changing other factors of health and, along with diet, exercise and sunshine and clean air and water would definitely improve immune function, lower inflammation, and much else (sanitoriums prioritized such things as getting plenty of sunshine and dairy, both of which would increase vitamin D3 that is necessary for immunological health). Improvements in physical health, of course, would go hand in hand with that of mental health. An example of this is that winter conceptions, when vitamin D3 production is low, result in higher rates later on of childhood learning disabilities and other problems in neurocognitive development (BBC, Learning difficulties linked with winter conception).

As a side note, physical development was tied up with gender issues and gender roles, especially for boys in becoming men. There became a fear that the newer generations of urban youth were failing to develop properly, physically and mentally, morally and socially. Fitness became a central concern for the civilizational project and it was feared that we modern humans might fail this challenge. Most galling of all was ‘feminization’, not only about loss of an athletic build but loss of something to the masculine psychology, involving the depression and anxiety, sensitivity and weakness of conditions like neurasthenia while also overlapping with tubercular consumption. Some of this could be projected onto racial inferiority, far from being limited to the distinction between those of European descent and all others for it also was used to divide humanity up in numerous ways (German vs French, English vs Irish, North vs South, rich vs poor, Protestants vs Catholics, Christians vs Jews, etc).

Gender norms were applied to all aspects of health and development, including perceived moral character and personality disposition. This is a danger to the individual, but also potentially a danger to society. “Here we can return for the moment to the notion that the male Jew is feminized like the male tubercular. The tubercular’s progressive feminization begins in the middle of the nineteenth century with the introduction of the term: infemminire, to feminize, which is supposedly a result of male castration. By the 1870s, the term is used to describe the feminisme of the male through the effects of other disease, such as tuberculosis. Henry Meige, at the Salpetriere, saw this feminization as an atavism, in which the male returns to the level of the “sexless” child. Feminization is therefore a loss, which can cause masturbation and thus illness in certain predisposed individuals. It is also the result of actual castration or its physiological equivalent, such as an intensely debilitating illness like tuberculosis, which reshapes the body” (Sanders L. Gilman, Franz Kafka, the Jewish Patient). There was a fear that all of civilization was becoming effeminate, especially among the upper classes who were expected to be the leaders. That was the entire framework of neurasthenia-obsessed rhetoric in late nineteenth to early twentieth century America. The newer generations of boys, the argument went, were somehow deficient and inadequate. Looking back on that period, there is no doubt that physical and mental illness was increasing, while bone structure was becoming underdeveloped in a way one could perceive as effeminate; such bone development problems are particularly obvious among children raised on plant-based diets, especially veganism and near-vegan vegetarianism, but also anyone on a diet lacking nutritious animal foods.

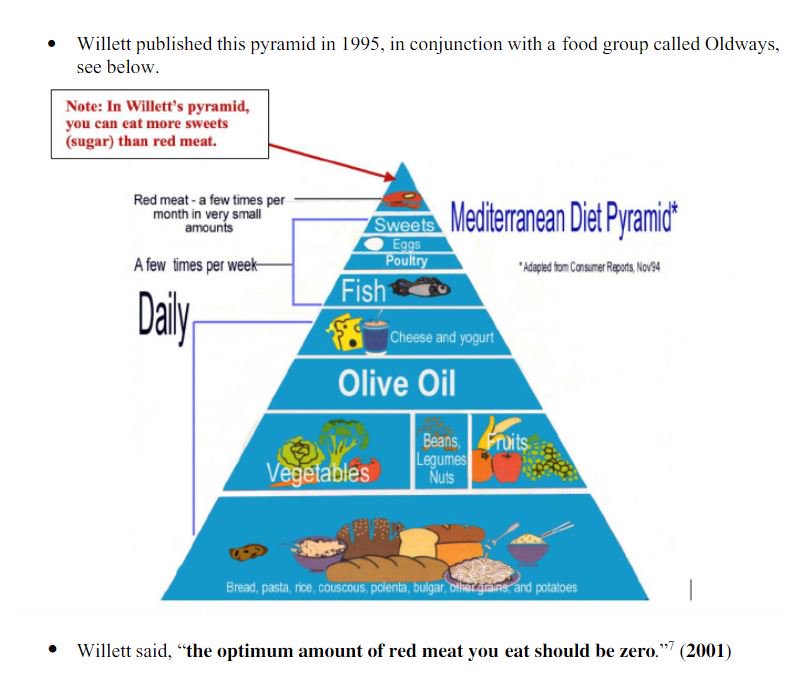

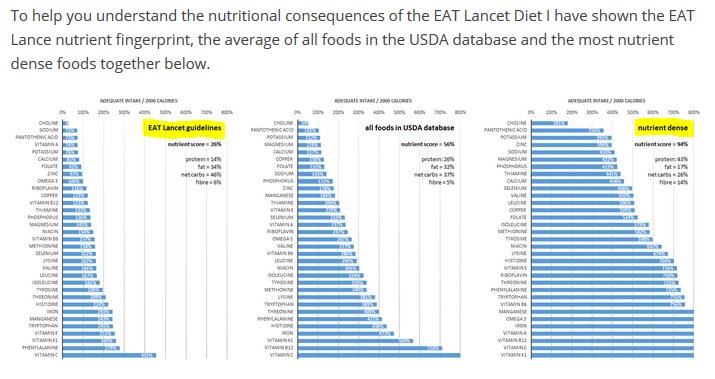

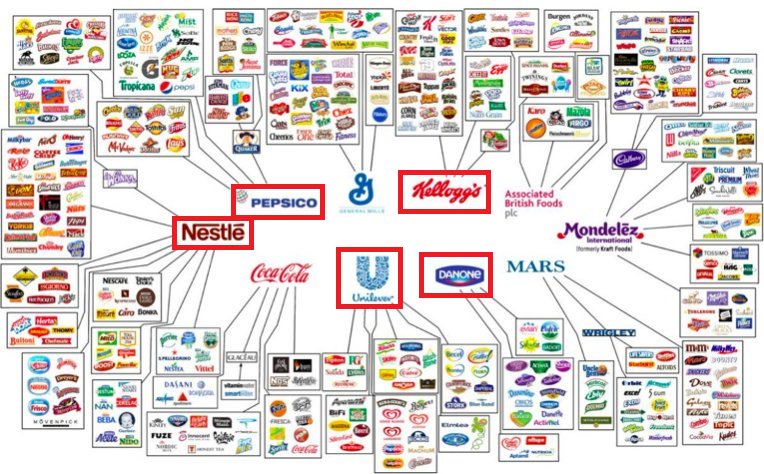

Let me make one odd connection before moving on. The Seventh Day Adventist Dr. John Harvey Kellogg believed masturbation was both a moral sin and a cause of ill health but also a sign of inferiority, and his advocacy of a high-fiber vegan diet including breakfast cereals was based on the Galenic theory that such foods decreased libido. Dr. Kellogg was also an influential eugenicist and operated a famous sanitorium. He wasn’t alone in blaming masturbation for disease. The British Dr. D. G. Macleod Munro treated masturbation as a contributing factor for tuberculosis: “the advent of the sexual appetite in normal adolescence has a profound effect upon the organism, and in many cases when uncontrolled, leads to excess about the age when tuberculosis most frequently delivers its first open assault upon the body,” as quoted by Gilman. This related to the ‘bankruptcy’ Kafka mentioned, the idea that one could waste one’s energy reserves. Maybe there is an insight in this belief, despite it being misguided and misinterpreted. The source of the ‘bankruptcy’ may have in part been a nutritional debt and certainly a high-fiber vegan diet would not refill ones energy and nutrient reserves as an investment in one’s health — hence, the public health risk of what one might call a hyper-agricultural diet as exemplified by the USDA dietary recommendations and corporate-backed dietary campaigns like EAT-Lancet (Dietary Dictocrats of EAT-Lancet; & Corporate Veganism), but it’s maybe reversing course, finally (Slow, Quiet, and Reluctant Changes to Official Dietary Guidelines; American Diabetes Association Changes Its Tune; & Corporate Media Slowly Catching Up With Nutritional Studies).

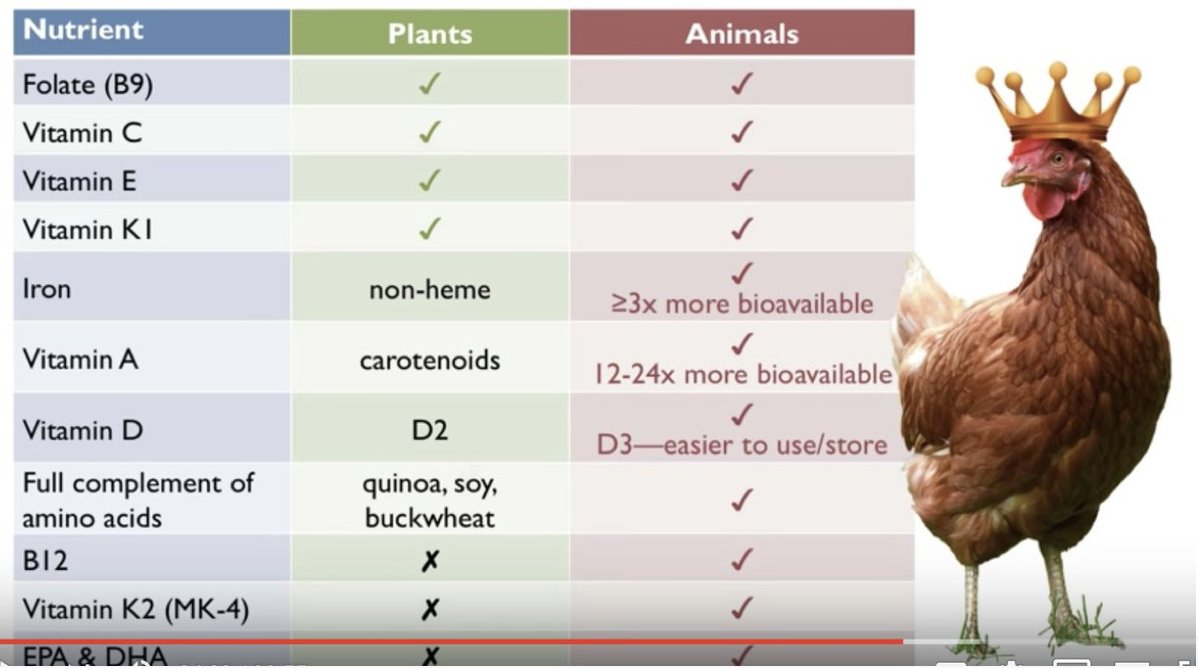

So far, my focus has mostly been on what we ingest or are otherwise exposed to because of agriculture and the food system, in general and more specifically in industrialized society with its refined, processed, and adulterated foods, largely from plants. But the other side of the picture is what our diet is lacking, what we are deficient in. As I touched upon directly above, an agricultural diet hasn’t only increased certain foods and substances but simultaneously decreased others. What promoted optimal health throughout human evolution has, in many cases, been displaced or interrupted. Agriculture is highly destructive and has depleted the nutrient-level in the soil (Carnivore Is Vegan) and, along with this, even animal foods as part of the agricultural system are similarly depleted of nutrients as compared to animal foods from pasture or free-range. For example, fat-soluble vitamins (true vitamin A as retinol, vitamin D3, vitamin K2 not to be confused with K1, and vitamin E complex) are not found in plant foods and are found in far less concentration with foods from animals from factory-farming or from grazing on poor soil from agriculture, especially the threat of erosion and desertification. Rhonda Patrick points to deficiencies of vitamin D3, EPA and DHA and hence insufficient serotonin levels as being causally linked to autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, etc (TheIHMC, Rhonda Patrick on Diet-Gene Interactions, Epigenetics, the Vitamin D-Serotonin Link and DNA Damage). She also discusses inflammation, epigenetics, and DNA damage which relates to the work by others (Dr. Catherine Shanahan On Dietary Epigenetics and Mutations).

One of the biggest changes with agriculture was the decrease of fatty animal foods that were nutrient-dense and nutrient-bioavailable. It’s in the fat that are found the fat-soluble vitamins and fat is necessary for their absorption (i.e., fat-soluble), and these key nutrients relate to almost everything else such as minerals as calcium and magnesium that also are found in animal foods (Calcium: Nutrient Combination and Ratios); the relationship of seafood with the balance of sodium, magnesium, and potassium is central (On Salt: Sodium, Trace Minerals, and Electrolytes) and indeed populations that eat more seafood live longer. These animal foods used to hold the prized position in the human diet and the earlier hominid diet as well, as part of our evolutionary inheritance from millions of years of adaptation to a world where fatty animals once were abundant (J. Tyler Faith, John Rowan & Andrew Du, Early hominins evolved within non-analog ecosystems). That was definitely true in the paleolithic before the megafauna die-off, but even to this day hunter-gatherers when they have access to traditional territory and prey will seek out the fattest animals available, entirely ignoring lean animals because rabbit sickness is worse than hunger (humans can always fast for many days or weeks, if necessary, and as long as they have reserves of body fat they can remain perfectly healthy).

We’ve already discussed autism in terms of many other dietary factors, especially excesses of otherwise essential nutrients like glutamate, propionate, and butyrate. But like most modern people, those on the autistic spectrum can be nutritionally deficient in other ways and unsurprisingly that would involve fat-soluble vitamins. In a fascinating discussion one of her more recent books, Nourishing Fats, Sally Fallon Morell offers a hypothesis of an indirect causal mechanism. First off, she notes that, “Dr. Mary Megson of Richmond, Virginia, had noticed that night blindness and thyroid conditions—both signs of vitamin A deficiency—were common in family members of autistic children” (p. 156), and so indicating a probable deficiency of the same in the affected child. This might be why supplementing cod liver oil, high in true vitamin A, helps with autistic issues. “As Dr. Megson explains, in genetically predisposed children, autism is linked to a G-alpha protein defect. G-alpha proteins form one of the most prevalent signaling systems in our cells, regulating processes as diverse as cell growth, hormonal regulation and sensory perception—like seeing” (p. 157).

The sensory issues common among autistics may seem to be neurocognitive in origin, but the perceptual and psychological effects may be secondary to the real cause in altered eye development. Because the rods in their eyes don’t function properly, they have distorted vision that is experienced as a blurry and divided visual field, like a magic-eye puzzle, that takes constant effort in making coherent sense of the world around them. “According to Megson, the blocked visual pathways explain why children on the autism spectrum “melt down” when objects are moved or when you clean up their lines or piles of toys sorted by color They work hard to piece together their world; it frightens and overwhelms them when the world as they are able to see it changes. It also might explain why children on the autism spectrum spend time organizing tings so carefully. It’s the only way they can “see” what’s out there” (p. 157). The rods at the edge of their vision work better and so they prefer to not look directly at people.

The vitamin A link is not merely speculative. In other aspects seen in autism, studies have sussed out some of the proven and possible factors and mechanisms: “Decreased vitamin A, and its retinoic acid metabolites, lead to a decrease in CD38 and associated changes that underpin a wide array of data on the biological underpinnings of ASD, including decreased oxytocin, with relevance both prenatally and in the gut. Decreased sirtuins, poly-ADP ribose polymerase-driven decreases in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), hyperserotonemia, decreased monoamine oxidase, alterations in 14-3-3 proteins, microRNA alterations, dysregulated aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity, suboptimal mitochondria functioning, and decreases in the melatonergic pathways are intimately linked to this. Many of the above processes may be modulating, or mediated by, alterations in mitochondria functioning. Other bodies of data associated with ASD may also be incorporated within these basic processes, including how ASD risk factors such as maternal obesity and preeclampsia, as well as more general prenatal stressors, modulate the likelihood of offspring ASD” (Michael Maes et al, Integrating Autism Spectrum Disorder Pathophysiology: Mitochondria, Vitamin A, CD38, Oxytocin, Serotonin and Melatonergic Alterations in the Placenta and Gut). By the way, some of those involved pathways are often discussed in terms of longevity, which indicates autistics might be at risk for shortened lifespan. Autism, indeed, is comorbid with numerous other health issues and genetic syndromes. So autism isn’t just an atypical expression on a healthy spectrum of neurodiversity.

The affect of the agricultural diet, especially in its industrially-processed variety, has a powerful impact on numerous systems simultaneously, as autism demonstrates. There is unlikely any single causal factor and causal mechanism with most other health conditions as well. We can take this a step further. With historical changes in diet, it wasn’t only fat-soluble vitamins that were lost. Humans traditionally ate nose-to-tail and this brought with it a plethora of nutrients, even some thought of as being only sourced from plant foods. In its raw or lightly cooked form, meat has more than enough vitamin C for a low-carb diet; whereas a high-carb diet, since glucose competes with vitamin C, requires higher intake of this antioxidant which can lead to deficiencies at levels that otherwise would be adequate (Sailors’ Rations, a High-Carb Diet). Also, consider that prebiotics can be found in animal foods as well and animal-based prebiotics likely feeds a very different kind of microbiome that could shift so much else in the body, such as neurotransmitter production: “I found this list of prebiotic foods that were non-carbohydrate that included cellulose, cartilage, collagen, fructooligosaccharides, glucosamine, rabbit bone, hair, skin, glucose. There’s a bunch of things that are all — there’s also casein. But these tend to be some of the foods that actually have some of the highest prebiotic content,” from Vanessa Spina as quoted in Fiber or Not: Short-Chain Fatty Acids and the Microbiome).

Let’s briefly mention fat-soluble vitamins again in making a point about other animal-based nutrients. Fat-soluble vitamins, similar to ketosis and autophagy, have a profound effect on human biological functioning, including that of the mind (see the work of Weston A. Price as discussed in Health From Generation To Generation; also see the work of those described in Physical Health, Mental Health). In many ways, they are closer to hormones than mere nutrients, as they orchestrate entire systems in the body and how other nutrients get used, particularly seen with vitamin K2 that Weston A. Price discovered in calling it “Activator X” (only found in animal and fermented foods, not in whole or industrially-processed plant foods). I bring this up because some other animal-based nutrients play a similar important role. Consider glycine that is the main amino acid in collagen. It is available in connective tissues and can be obtained through soups and broths made from bones, skin, ligaments, cartilage, and tendons. Glycine is right up there with the fat-soluble vitamins in being central to numerous systems, processes, and organs.

As I’ve already discussed glutamate at great length, let me further that discussion by pointing out a key link. “Glycine is found in the spinal cord and brainstem where it acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter via its own system of receptors,” writes Afifah Hamilton. “Glycine receptors are ubiquitous throughout the nervous system and play important roles during brain development. [Ito, 2016] Glycine also interacts with the glutaminergic neurotransmission system via NMDA receptors, where both glycine and glutamate are required, again, chiefly exerting inhibitory effects” (10 Reasons To Supplement With Glycine). Hamilton elucidates the dozens of roles played by this master nutrient and the diverse conditions that follow from its deprivation or insufficiency — it’s implicated in obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and alcohol use disorder, along with much else such as metabolic syndrome. But it’s being essential to glutamate really stands out for this discussion. “Glutathione is synthesised,” Hamilton further explains, “from the amino acids glutamate, cysteine, and glycine, but studies have shown that the rate of synthesis is primarily determined by levels of glycine in the tissue. If there is insufficient glycine available the glutathione precursor molecules are excreted in the urine. Vegetarians excrete 80% more of these precursors than their omnivore counterparts indicating a more limited ability to complete the synthesis process.” Did you catch what she is saying there? Autistics already have too much glutamate and, if they are deficient in glycine, they won’t be able to convert glutamate into the important glutathione. When the body is overwhelmed with unused glutamate, it does what it can to eliminate them, but when constantly flooded with high-glutamate intake it can’t keep up. The excess glutamate then wreaks havoc on neurocognitive functioning.

The whole mess of the agricultural diet, specifically in its modern industrialized form, has been a constant onslaught taxing our bodies and minds. And the consequences are worsening with each generation. What stands out to me about autism, in particular, is how isolating it is. The repetitive behavior and focus on objects to the exclusion of human relationships resonates with how addiction isolates the individual. As with other conditions influenced by diet (shizophrenia, ADHD, etc), both autism and addiction block normal human relating in creating an obsessive mindset that, in the most most extreme forms, blocks out all else. I wonder if all of us moderns are simply expressing milder varieties of this biological and neurological phenomenon (Afifah Hamilton, Why No One Should Eat Grains. Part 3: Ten More Reasons to Avoid Wheat). And this might be the underpinning of our hyper-individualistic society, with the earliest precursors showing up in the Axial Age following what Julian Jaynes hypothesized as the breakdown of the much more other-oriented bicameral mind. What if our egoic consciousness with its rigid psychological boundaries is the result of our food system, as part of the civilizational project of mass agriculture?

* * *

Mongolian Diet and Fasting:

“Heaven grew weary of the excessive pride and luxury of China… I am from the Barbaric North. I wear the same clothing and eat the same food as the cowherds and horse-herders. We make the same sacrifices and we share our riches. I look upon the nation as a new-born child and I care for my soldiers as though they were my brothers.”

~Genghis Khan, letter of invitation to Ch’ang Ch’un

For anyone who is curious to learn more, the original point of interest was a quote by Jack Weatherford in his book Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. He wrote that, “The Chinese noted with surprise and disgust the ability of the Mongol warriors to survive on little food and water for long periods; according to one, the entire army could camp without a single puff of smoke since they needed no fires to cook. Compared to the Jurched soldiers, the Mongols were much healthier and stronger. The Mongols consumed a steady diet of meat, milk, yogurt, and other diary products, and they fought men who lived on gruel made from various grains. The grain diet of the peasant warriors stunted their bones, rotted their teeth, and left them weak and prone to disease. In contrast, the poorest Mongol soldier ate mostly protein, thereby giving him strong teeth and bones. Unlike the Jurched soldiers, who were dependent on a heavy carbohydrate diet, the Mongols could more easily go a day or two without food.” By the way, that biography was written by an anthropologist who lived among and studied the Mongols for years. It is about the historical Mongols, but filtered through the direct experience of still existing Mongol people who have maintained a traditional diet and lifestyle longer than most other populations.

As nomadic herders living on arid grasslands with no option of farming, they had limited access to plant foods from foraging and so their diet was more easily applied to horseback warfare, even over long distances when food stores ran out. That meant, when they had nothing else, on “occasion they will sustain themselves on the blood of their horses, opening a vein and letting the blood jet into their mouths, drinking till they have had enough, and then staunching it.” They could go on “quite ten days like this,” according to Marco Polo’s observations. “It wasn’t much,” explained Logan Nye, “but it allowed them to cross the grasses to the west and hit Russia and additional empires. […]On the even darker side, they also allegedly ate human flesh when necessary. Even killing the attached human if horses and already-dead people were in short supply” (How Mongol hordes drank horse blood and liquor to kill you). The claim of their situational cannibalism came from the writings of Giovanni da Pian del Carpini who noted they’d eat anything, even lice. The specifics of what they ate was also determined by season: “Generally, the Mongols ate dairy in the summer, and meat and animal fat in the winter, when they needed the protein for energy and the fat to help keep them warm in the cold winters. In the summers, their animals produced a lot of milk so they switched the emphasis from meat to milk products” (from History on the Net, What Did the Mongols Eat?). In any case, animal foods were always the staple.

By the way, some have wondered how long humans have been consuming dairy, since the gene for lactose tolerance is fairly recent. In fact, “a great many Mongolians, both today and in Genghis Khan’s time are lactose intolerant. Fermentation breaks down the lactose, removing it almost entirely, making it entirely drinkable to the Mongols” (from Exploring History, Food That Conquered The World: The Mongols — Nomads And Chaos). Besides mare’s milk fermented into alcohol, they had a wide variety of other cultured dairy and aged cheese. Even then, much of the dairy would contain significant amounts of lactose. A better explanation is that many of the dairy-loving microbes have been incorporated into the Mongolian microbiome, and these microbes in combination as a microbial ecosystem do some combination of: digest lactose, moderate the effects of lactose intolerance, and/or somehow alter the body’s response to lactose. But looking at a single microbe might not tell us much. “Despite the dairy diversity she saw,” wrote Andrew Curry, “an estimated 95 percent of Mongolians are, genetically speaking, lactose intolerant. Yet, in the frost-free summer months, she believes they may be getting up to half their calories from milk products. […] Rather than a previously undiscovered strain of microbes, it might be a complex web of organisms and practices—the lovingly maintained starters, the milk-soaked felt of the yurts, the gut flora of individual herders, the way they stir their barrels of airag—that makes the Mongolian love affair with so many dairy products possible” (The answer to lactose intolerance might be in Mongolia).

Here is what is interesting. Based on study of ancient corpses, it’s been determined that lactose intolerant people in this region have been including dairy in their diet for 5,000 years. It’s not limited to the challenge of lactose intolerant people depending on a food staple that is abundant in lactose. The Mongolian population also has high rates of carrying the APOE4 gene variation that can make problematic a diet high in saturated fat (Helena Svobodová et al, Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism in the Mongolian population). That is a significant detail, considering dairy has a higher amount of saturated fat than any other food. These people should be keeling over with nearly every disease known to humanity, particularly as they commonly drink plenty of alcohol and smoke tobacco (as was likewise true of the heart-healthy and long-lived residents of mid-20th century Roseto, Pennsylvania with their love of meat, lard, alcohol, and tobacco; see Blue Zones Dietary Myth). Yet, it’s not the traditional Mongolians but the the industrialized Mongolians who show all the health problems. A major difference between these two populations in Mongolia is diet, much of it being a difference of much low-carb animal foods eaten versus the amount of high-carb plant foods. Genetics are not deterministic, not in the slightest. As some others have noted, the traditional Mongolian diet would be accurately described as a low-carb paleo diet that, in the wintertime, would often have been a strict carnivore diet and ketogenic diet; although even rural Mongolians, unlike in the time of Genghis Khan, now get a bit more starchy agricultural foods. Maybe there is a protective health factor found in a diet that relies on nutrient-dense animal foods and leans toward the ketogenic.

It isn’t only that the Mongolian diet was likely ketogenic because of being low-carbohydrate, particularly on their meat-based winter diet, but also because it involved fasting. From Mongolia Volume 1 The Tangut Country, and the Solitudes of Northernin (1876), Nikolaĭ Mikhaĭlovich Przhevalʹskiĭ writes in the second note on p. 65 under the section Calendar and Year-Cycle: “On the New Year’s Day, or White Feast of the Mongols, see ‘Marco Polo’, 2nd ed. i. p. 376-378, and ii. p. 543. The monthly fetival days, properly for the Lamas days of fasting and worship, seem to differ locally. See note in same work, i. p. 224, and on the Year-cycle, i. p. 435.” This is alluded to in another text, in describing that such things as fasting were the norm of that time: “It is well known that both medieval European and traditional Mongolian cultures emphasized the importance of eating and drinking. In premodern societies these activities played a much more significant role in social intercourse as well as in religious rituals (e.g., in sacrificing and fasting) than nowadays” (Antti Ruotsala, Europeans and Mongols in the middle of the thirteenth century, 2001). A science journalist trained in biology, Dyna Rochmyaningsih, also mentions this: “As a spiritual practice, fasting has been employed by many religious groups since ancient times. Historically, ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Babylonians, and Mongolians believed that fasting was a healthy ritual that could detoxify the body and purify the mind” (Fasting and the Human Mind).

Mongol shamans and priests fasted, no different than in so many other religions, but so did other Mongols — more from Przhevalʹskiĭ’s 1876 account showing the standard feast and fast cycle of many traditional ketogenic diets: “The gluttony of this people exceeds all description. A Mongol will eat more than ten pounds of meat at one sitting, but some have been known to devour an average-sized sheep in twenty-four hours! On a journey, when provisions are economized, a leg of mutton is the ordinary daily ration for one man, and although he can live for days without food, yet, when once he gets it, he will eat enough for seven” (see more quoted material in Diet of Mongolia). Fasting was also noted of earlier Mongols, such as Genghis Khan: “In the spring of 2011, Jenghis Khan summoned his fighting forces […] For three days he fasted, neither eating nor drinking, but holding converse with the gods. On the fourth day the Khakan emerged from his tent and announced to the exultant multitude that Heaven had bestowed on him the boon of victory” (Michael Prawdin, The Mongol Empire, 1967). Even before he became Khan, this was his practice as was common among the Mongols, such that it became a communal ritual for the warriors:

“When he was still known as Temujin, without tribe and seeking to retake his kidnapped wife, Genghis Khan went to Burkhan Khaldun to pray. He stripped off his weapons, belt, and hat – the symbols of a man’s power and stature – and bowed to the sun, sky, and mountain, first offering thanks for their constancy and for the people and circumstances that sustained his life. Then, he prayed and fasted, contemplating his situation and formulating a strategy. It was only after days in prayer that he descended from the mountain with a clear purpose and plan that would result in his first victory in battle. When he was elected Khan of Khans, he again retreated into the mountains to seek blessing and guidance. Before every campaign against neighboring tribes and kingdoms, he would spend days in Burhkhan Khandun, fasting and praying. By then, the people of his tribe had joined in on his ritual at the foot of the mountain, waiting his return” (Dr. Hyun Jin Preston Moon, Genghis Khan and His Personal Standard of Leadership).

As an interesting side note, the Mongol population have been studied to some extent in one area of relevance. In Down’s Anomaly (1976), Smith et al writes that, “The initial decrease in the fasting blood sugar was greater than that usually considered normal and the return to fasting blood sugar level was slow. The results suggested increased sensitivity to insulin. Benda reported the initial drop in fating blood sugar to be normal but the absolute blood sugar level after 2 hours was lower for mongols than for controls.” That is probably the result of a traditional low-carb diet that had been maintained continuously since before history. For some further context, I noticed some discussion about the Mongolian keto diet (Reddit, r/keto, TIL that Ghenghis Khan and his Mongol Army ate a mostly keto based diet, consisting of lots of milk and cheese. The Mongols were specially adapted genetically to digest the lactase in milk and this made them easier to feed.) that was inspired by the scientific documentary “The Evolution of Us” (presently available on Netflix and elsewhere).

As a concluding thought, we may have the Mongols to thank for the modern American hamburger: “Because their cavalry was traveling so much, they would often eat while riding their horses towards their next battle. The Mongol soldiers would soften scraps of meat by placing it under their saddles while they rode. By the time the Mongols had time for a meal, the meat would be “tenderized” and consumed raw. […] By no means did the Mongols have the luxury of eating the kind of burgers we have today, but it was the first recorded time that meat was flattened into a patty-like shape” (Anna’s House, Brunch History: The Shocking Hamburger Origin Story You Never Heard; apparently based on the account of Jean de Joinville who was born a few years after Genghis Khan’s death). The Mongols introduced it to Russia, in what was called steak tartare (Tartars being one of the ethnic groups in the Mongol army), the Russians introduced it to Germany where it was most famously called hamburg steak (because sailors were served it at the ports of Hamburg), from which it was introduced to the United States by way of German immigrants sailing out of Hamburg. Another version of this is Salisbury steak that was invented during the American Civil War by Dr. James Henry Salisbury (physician, chemist, and medical researcher) as part of a meat-based, low-carb diet in medically and nutritionally treating certain diseases and ailments.

* * *

3/30/19 – An additional comment: I briefly mentioned sugar, that it causes a serotonin high and activates the hedonic pathway. I also noted that it was late in civilization when sources of sugar were cultivated and, I could add, even later when sugar became cheap enough to be common. Even into the 1800s, sugar was minimal and still often considered more as medicine than food.

To extend this thought, it isn’t only sugar in general but specific forms of it (Yu Hue, Fructose and glucose can regulate mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and lipogenic gene expression via distinct pathways). Fructose, in particular, has become widespread because of United States government subsidizing corn agriculture which has created a greater corn yield that humans can consume. So, what doesn’t get fed to animals or turned into ethanol, mostly is made into high fructose corn syrup and then added into almost every processed food and beverage imaginable.

Fructose is not like other sugars. This was important for early hominid survival and so shaped human evolution. It might have played a role in fasting and feasting. In 100 Million Years of Food, Stephen Le writes that, “Many hypotheses regarding the function of uric acid have been proposed. One suggestion is that uric acid helped our primate ancestors store fat, particularly after eating fruit. It’s true that consumption of fructose induces production of uric acid, and uric acid accentuates the fat-accumulating effects of fructose. Our ancestors, when they stumbled on fruiting trees, could gorge until their fat stores were pleasantly plump and then survive for a few weeks until the next bounty of fruit was available” (p. 42).

That makes sense to me, but he goes on to argue against this possible explanation. “The problem with this theory is that it does not explain why only primates have this peculiar trait of triggering fat storage via uric acid. After all, bears, squirrels, and other mammals store fat without using uric acid as a trigger.” This is where Le’s knowledge is lacking for he never discusses ketosis that has been centrally important for humans unlike other animals. If uric acid increases fat production, that would be helpful for fattening up for the next starvation period when the body returned to ketosis. So, it would be a regular switching back and forth between formation of uric acid that stores fat and formation of ketones that burns fat.

That is fine and dandy under natural conditions. Excess fructose on a continuous basis, however, is a whole other matter. It has been strongly associated with metabolic syndrome. One pathway of causation is that increased production of uric acid. This can lead to gout (wrongly blamed on meat) but other things as well. It’s a mixed bag. “While it’s true that higher levels of uric acid have been found to protect against brain damage from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis, high uric acid unfortunately increases the risk of brain stroke and poor brain function” (Le, p. 43).

The potential side effects of uric acid overdose are related to other problems I’ve discussed in relation to the agricultural mind. “A recent study also observed that high uric acid levels are associated with greater excitement-seeking and impulsivity, which the researchers noted may be linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)” (Le, p. 43). The problems of sugar go far beyond mere physical disease. It’s one more factor in the drastic transformation of the human mind.

* * *

4/2/19 – More info: There are certain animal fats, the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, that are essential to human health (Georgia Ede, The Brain Needs Animal Fat). These were abundant in the hunter-gatherer diet. But over the history of agriculture, they have become less common.

This is associated with psychiatric disorders and general neurocognitive problems, including those already mentioned above in the post. Agriculture and industrialization have replaced these healthy lipids with industrially-processed seed oils that are high in linoleic acid (LA), an omega-6 fatty acids. LA interferes with the body’s use of omega-3 fatty acids. Worse still, these seed oils appear to not only alter gene expression (epigenetics) but also to be mutagenic, a possible causal factor behind conditions like autism (Dr. Catherine Shanahan On Dietary Epigenetics and Mutations).

The loss of healthy animal fats in the diet might be directly related to numerous conditions. “Children who lack DHA are more likely to have increased rates of neurological disorders, in particular attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism” (Maria Cross, Why babies need animal fat). Also, trans fats found in industrial seed oils are linked to Alzheimer’s as well (Millie Barnes, Alzheimer’s Risk May be 75% Higher for People Who Eat Trans Fats; Takanori Honda et al, Serum elaidic acid concentration and risk of dementia: The Hisayama study).

“Biggest dietary change in the last 60 years has been avoidance of animal fat. Coincides with a huge uptick in autism incidence. The human brain is 60 percent fat by weight. Much more investigation needed on correspondence between autism and prenatal/child ingestion of dietary fat.”

~ Brad Lemley

The agricultural diet, along with a drop in animal foods, saw a loss of access to the high levels and full profile of B vitamins. As with the later industrial seed oils, this had a major impact on genetics:

“The phenomenon wherein specific traits are toggled up and down by variations in gene expression has recently been recognized as a result of the built-in architecture of DNA and dubbed “active adaptive evolution.” 44

“As further evidence of an underlying logic driving the development of these new autism-related mutations, it appears that epigenetic factors activate the hotspot, particularly a kind of epigenetic tagging called methylation. 45 In the absence of adequate B vitamins, specific areas of the gene lose these methylation tags, exposing sections of DNA to the factors that generate new mutations. In other words, factors missing from a parent’s diet trigger the genome to respond in ways that will hopefully enable the offspring to cope with the new nutritional environment. It doesn’t always work out, of course, but that seems to be the intent.”

~Catherine Shanahan, Deep Nutrition, p. 56

And one last piece of evidence on the essential nature of animal fats:

“Maternal intake of fish, a key source of fatty acids, has been investigated in association with child neurodevelopmental outcomes in several studies. […]

“Though speculative at this time, the inverse association seen for those in the highest quartiles of intake of ω-6 fatty acids could be due to biological effects of these fatty acids on brain development. PUFAs have been shown to be important in retinal and brain development in utero (37) and to play roles in signal transduction and gene expression and as components of cell membranes (38, 39). Maternal stores of fatty acids in adipose tissue are utilized by the fetus toward the end of pregnancy and are necessary for the first 2 months of life in a crucial period of development (37). The complex effects of fatty acids on inflammatory markers and immune responses could also mediate an association between PUFA and ASD. Activation of the maternal immune system and maternal immune aberrations have been previously associated with autism (5, 40, 41), and findings suggest that increased interleukin-6 could influence fetal brain development and increase risk of autism and other neuropsychiatric conditions (42–44). Although results for effects of ω-6 intake on interleukin-6 levels are inconsistent (45, 46), maternal immune factors potentially could be affected by PUFA intake (47). […]

“Our results provide preliminary evidence that increased maternal intake of ω-6 fatty acids could reduce risk of offspring ASD and that very low intakes of ω-3 fatty acids and linoleic acid could increase risk.”

~Kristen Lyall et al, Maternal Dietary Fat Intake in Association With Autism Spectrum Disorders

* * *

6/13/19 – About the bicameral mind, I saw some other evidence for it in relationship to fasting. In the following quote, it is described that after ten days of fasting ancient humans would experience spirits. One thing for certain is that one can be fully in ketosis in three days. This would be true even if it wasn’t total fasting, as the caloric restriction would achieve the same end.

The author, Michael Carr, doesn’t think fasting was the cause of the spirit visions, but he doesn’t explain the reason(s) for his doubt. There is a long history of fasting used to achieve this intended outcome. If fasting was ineffective for this purpose, why has nearly every known traditional society for millennia used such methods? These people knew what they were doing.

By the way, imbibing alcohol after the fast would really knock someone into an altered state. The body becomes even more sensitive to alcohol when in ketogenic state during fasting. Combine this altered state with ritual, setting, cultural expectation, and archaic authorization. I don’t have any doubt that spirit visions could easily be induced.

Reflections on the Dawn of Consciousness

ed. by Marcel Kuijsten

Kindle Location 5699-5718

Chapter 13

The Shi ‘Corpse/ Personator’ Ceremony in Early China

by Michael Carr

“”Ritual Fasts and Spirit Visions in the Liji” 37 examined how the “Record of Rites” describes zhai 齋 ‘ritual fasting’ that supposedly resulted in seeing and hearing the dead. This text describes preparations for an ancestral sacrifice that included divination for a suitable day, ablution, contemplation, and a fasting ritual with seven days of sanzhai 散 齋 ‘relaxed fasting; vegetarian diet; abstinence (esp. from sex, meat, or wine)’ followed by three days of zhizhai 致 齋 ‘strict fasting; diet of grains (esp. gruel) and water’.

“Devoted fasting is inside; relaxed fasting is outside. During fast-days, one thinks about their [the ancestor’s] lifestyle, their jokes, their aspirations, their pleasures, and their affections. [After] fasting three days, then one sees those [spirits] for whom one fasted. On the day of the sacrifice, when one enters the temple, apparently one must see them at the spirit-tablet. When one returns to go out the door [after making sacrifices], solemnly one must hear sounds of their appearance. When one goes out the door and listens, emotionally one must hear sounds of their sighing breath. 38

“This context unequivocally uses biyou 必 有 ‘must be/ have; necessarily/ certainly have’ to describe events within the ancestral temple; the faster 必 有 見 “must have sight of, must see” and 必 有 聞 “must have hearing of, must hear” the deceased parent. Did 10 days of ritual fasting and mournful meditation necessarily cause visions or hallucinations? Perhaps the explanation is extreme or total fasting, except that several Liji passages specifically warn against any excessive fasts that could harm the faster’s health or sense perceptions. 39 Perhaps the explanation is inebriation from drinking sacrificial jiu 酒 ‘( millet) wine; alcohol’ after a 10-day fast. Based on measurements of bronze vessels and another Liji passage describing a shi personator drinking nine cups of wine, 40 York University professor of religious studies Jordan Paper calculates an alcohol equivalence of “between 5 and 8 bar shots of eighty-proof liquor.” 41 On the other hand, perhaps the best explanation is the bicameral hypothesis, which provides a far wider-reaching rationale for Chinese ritual hallucinations and personation of the dead.”

* * *

7/16/19 – One common explanation for autism is the extreme male brain theory. A recent study may have come up with supporting evidence (Christian Jarrett, Autistic boys and girls found to have “hypermasculinised” faces – supporting the Extreme Male Brain theory). Autistics, including females, tend to have hypermasculinised. This might be caused by greater exposure to testosterone in the womb.

This made my mind immediately wonder how this relates. Changes in diets alter hormonal functioning. Endocrinology, the study of hormones, has been a major part of the diet debate going back to European researchers from earlier last century (as discussed by Gary Taubes). Diet affects hormones and hormones in turn affect diet. But I had something more specific in mind.

What about propionate and glutamate? What might their relationship be to testosterone? In a brief search, I couldn’t find anything about propionate. But I did find some studies related to glutamate. There is an impact on the endocrine system, although these studies weren’t looking at the results in terms of autism specifically or neurocognitive development in general. It points to some possibilities, though.

One could extrapolate from one of these studies that increased glutamate in the pregnant mother’s diet could alter what testosterone does to the developing fetus, in that testosterone increases the toxicity of glutamate which might not be a problem under normal conditions of lower glutamate levels. This would be further exacerbated during breastfeeding and later on when the child began eating the same glutamate-rich diet as the mother.

Testosterone increases neurotoxicity of glutamate in vitro and ischemia-reperfusion injury in an animal model

by Shao-Hua Yang et al

Effect of Monosodium Glutamate on Some Endocrine Functions

by Yonetani Shinobu and Matsuzawa Yoshimasa

* * *

11/28/21 – Here is some discussion of vitamin B1 (thiamin/thiamine). It couldn’t easily fit into the above post without revising and rewriting some of it. And it could’ve been made into a separate post by itself. But, for the moment, we’ll look at some of the info here, as relevant to the above survey and analysis. This section will be used as a holding place for some developing thoughts, although we’ll try to avoid getting off-topic in a post that is already too long. Nonetheless, we are going to have to trudge a bit into the weeds so as to see the requisite details more clearly.

Related to autism, consider this highly speculative hypothesis: “Thiamine deficiency is what made civilization. Grains deplete it, changing the gut flora to make more nervous and hyperfocused (mildly autistic) humans who are afraid to stand out. Conformity. Specialization in the division of labor” (JJ, Is Thiamine Deficiency Destroying Your Digestive Health? Why B1 Is ESSENTIAL For Gut Function, EONutrition). Thiamine deficiency is also associated with delirium and psychosis, such as schizophrenia (relevant scientific papers available are too numerous to be listed). By the way, psychosis, along with mania, has an established psychological and neurocognitive overlap with measures of modern conservatism; in opposition to the liberal link to mood disorders, addiction, and alcoholism (Uncomfortable Questions About Ideology; & Radical Moderates, Depressive Realism, & Visionary Pessimism). This is part of some brewing thoughts that won’t be further pursued here.

The point is simply to emphasize the argument that modern ideologies, as embodied worldviews and social identities, may partly originate in or be shaped by dietary and nutritional factors, among much else in modern environments and lifestyles. Nothing even comparable to conservatism and liberalism existed as such prior to the expansion and improvement of agriculture during the Axial Age (farm fields were made more uniform and well-managed, and hence with higher yields; e.g., systematic weeding became common as opposed to letting fields grow in semi-wild state); and over time there were also innovations in food processing (e.g., removing hulls from grains made them last longer in storage while having the unintended side effect of also removing a major source of vitamin B1 to help metabolize carbs).

In the original writing of this post, one focus was on addiction. Grains and dairy were noted as sources of exorphins and dopaminergic peptides, as well as propionate and glutamate. As already explained, this goes a long way to explain the addictive quality of these foods and their relationship to the repetitive behavior of obsessive-compulsive disorder. This is seen in many psychiatric illnesses and neurocognitive conditions, including autism (Derrick Lonsdale et al, Dysautonomia in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Case Reports of a Family with Review of the Literature):

“It has been hypothesized that autism is due to mitochondrial dysfunction [49], supported more recently [50]. Abnormal thiamine homeostasis has been reported in a number of neurological diseases and is thought to be part of their etiology [51]. Blaylock [52] has pointed out that glutamate and aspartate excitotoxicity is more relevant when there is neuron energy failure. Brain damage from this source might be expected in the very young child and the elderly when there is abnormal thiamine homeostasis. In thiamine-deficient neuroblastoma cells, oxygen consumption decreases, mitochondria are uncoupled, and glutamate, formed from glutamine, is no longer oxidized and accumulates [53]. Glutamate and aspartate are required for normal metabolism, so an excess or deficiency are both abnormal. Plaitakis and associates [54] studied the high-affinity uptake systems of aspartate/glutamate and taurine in synaptosomal preparations isolated from brains of thiamine-deficient rats. They concluded that thiamine deficiency could impair cerebellar function by inducing an imbalance in its neurotransmitter systems.”